Iraq’s political process is about to produce the least representative government since the country’s first election in 2005.

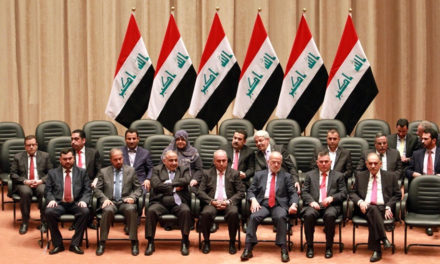

Earlier this month Iraqi political parties took important steps toward forming the next government, electing a president and designating a prime minister. Although the selection of Barham Salih and Adil Abdul-Mahdi is viewed with a fair degree of optimism, it’s too early to predict how the government, which could potentially, and partially see the light this week, will perform. So far, the delays, the horse trading and the multitude of dire security, economic and governance challenges awaiting the government paint a picture that’s within the norms, by local standards.

Two things are not, and they set this government apart from its predecessors: the exceptional distance separating its leaders from the electorate, and the absence of a real ruling coalition.

These shifts have potentially serious implications for the trajectory of democracy in Iraq. Keeping in mind that in parliamentary democracies it is not uncommon to have coalition governments involving multiple parties that individually don’t command a majority, Iraq still takes this a bit too far.

In Iraq’s case, there is no clear ruling alliance to speak of. Instead, a fluid group of factions and individuals with no common guiding principles among them, agreed on appointing individuals who, though reputable, were not elected, to hold the highest executive offices of president and prime minister. The largest of these groups, Moqtada al-Sadr’s Sairoon, controls barely 16% of the seats in parliament. Representation is further attenuated by the fact that the May 12 elections saw the lowest turnout in Iraq’s young democracy. The government formation process may reflect many things, but the will of the majority is not one of them.

Let’s consider these facts: put together, the two parties to which Speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi and President Barham Salih belong have 12 out of 329 seats in parliament. Adil Abdul-Mahdi, the Prime Minister-Designate, has none of his own to lean on. Two terms prior, in 2010, the blocs that produced the counterparts of today’s leaders (former Speaker Nujaifi, late President Talabani and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki) commanded roughly 220 seats.

Then consider these numbers: in 2010, Maliki and Nujaifi, as individuals, won 622,000 and 274,000 votes, respectively. Iyad Allawi, who led the bloc that supported Nujaifi and was himself to assume a top strategy planning council in that government won 407,000 votes. Together, Allawi’s Iraqiya and Maliki’s State of Law blocs won the confidence of more than 5.6 million voters. This time around, Salih’s and Halbousi’s parties won fewer than 400,000 votes between the two of them. Salih soon abandoned his own party, while Abdul-Mahdi didn’t even run in the elections.

It is not clear what this will precisely mean down the road. Popularity does not alone produce good governance. Derailed by Maliki’s paranoia from its original path as a government of national partnership, the 2010 government did more to exacerbate, rather than address Iraq’s problems, and by 2014 it ran the country into the ground. But this does not change the fact that on day one, it was a government whose leading components enjoyed massive support among the electorate.

Similarly, the low votes cast for the 2018 leaders do not mean they are unpopular, lack qualifications or will inevitably underperform. As many Iraq watchers have pointed out, President Salih is a respected reformist and intellectual figure in the eyes of many inside Iraq and abroad, and Abdul-Mahdi is also often praised for pragmatism, economic acumen, and thus far disinterest in clinging to power.

Yet a nagging question rears its ugly head: what motivated the political elites and entrenched interests to elevate leaders who might threaten their interests? What’s in it for them?

This brings us back to the other troubling issue, Abdul-Mahdi wasn’t presented as the candidate of a specific largest bloc seeking to promote a specific set of policies. Instead, he’s a compromise candidate who perfectly fits the trend established for selecting prime ministers since 2005 – look for the seemingly bookish, least threatening man in the room, a man who does not command a militia and who seems least objectionable to the various stakeholders and make him prime minister.

In the short-term, this means that Abdul-Mahdi will be under competing pressures from all powerful parties seeking to maximize their role in the cabinet as a means to generate the revenue essential to maintaining and expanding their patronage networks. Such pressure is already presenting obstacles, threatening to dilute Abdul-Mahdi’s stated goal of an independent cabinet with party appointees, and possibly force him to present a partial cabinet until further compromises are possible.

Even assuming that Abdul-Mahdi will succeed in getting a cabinet confirmed, what will happen down the road if the agendas of Muqtada al-Sadr and Hadi al-Amiri align on policies that Abdul-Mahdi opposes? Given their mutual deep hostility to the U.S., we can reasonably expect Sadr and Amiri decide to work together in parliament to terminate security cooperation with the U.S. and other Western nations. Will Abdul-Mahdi’s views to the contrary matter?

One thing we know for sure, the next four years are built on weak foundations and the prime minister and president won’t have a strong mandate to act independent of the transactional politics and balance of power among the power brokers behind them.

With all this in mind, there are two broad directions in which government affairs can go from here. In one possibility, Abdul-Mahdi is trapped between competing centers of power, especially Muqtada al-Sadr and Hadi al-Amiri. If a prolonged deadlock plagues government formation or its business in the near term, Abdul-Mahdi may be removed, or may resign and the process resets.

In the other, the new cabinet obediently serves the policies of the power brokers and entrenched interests through compromises. Little progress on governance, services or fighting corruption can be expected. As public grievances mount amid government incompetence, Iraq may descend into another outburst of violent protests next summer, with yet another chance for mismanagement to produce disaster.

The 2010 government formation was a lost chance for consolidating democratic and effective governance. This term is so far shaping up to be the beginning of the end for democracy and a harbinger for another cycle of failure and tumult.

Omar Al-Nidawi

Omar Al-Nidawi is an Iraq analyst based in Washington D.C. and he is a fellow with the Truman National Security Project. The views expressed here are his own.