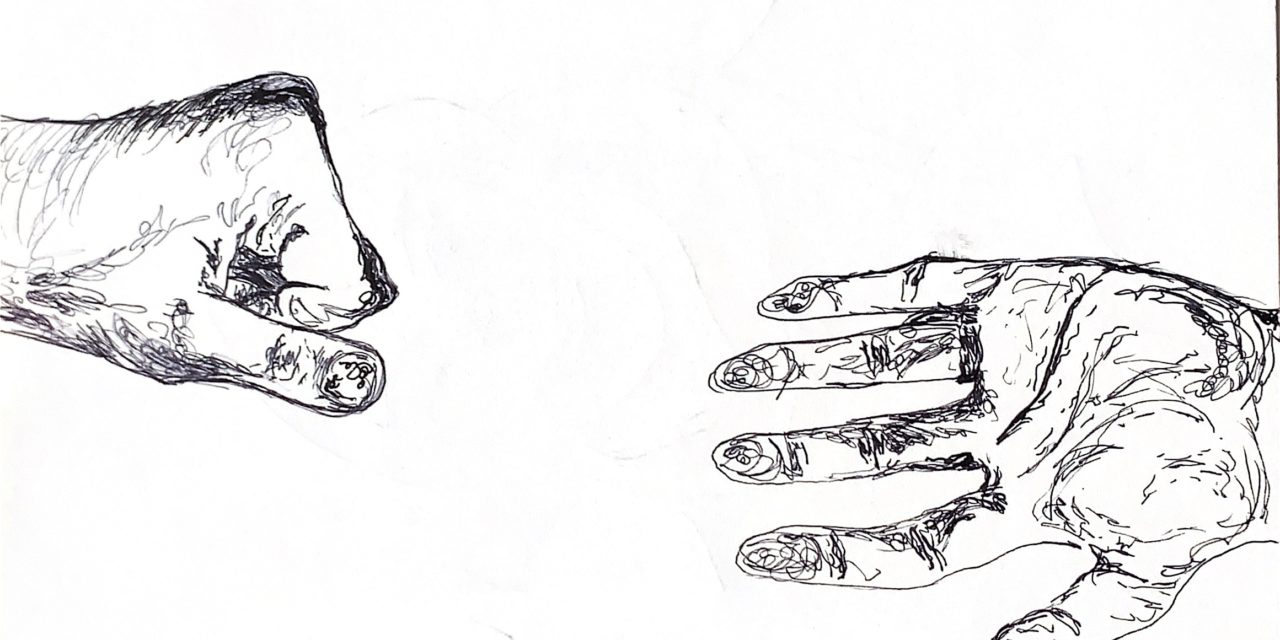

(Sketch by Mariam Hassoun: The illustration is meant to express how aid to IDPs was so fickle: they usually were met with a closed fist from the government and, over time, from NGOs, but relied on the open hands/generosity of their community)

If you declare a crisis over, does it disappear? This seems to be the Iraqi government’s strategy with regards to internally displaced persons (IDPs) and their educational opportunities, or lack thereof. In the past few years, the Iraqi government has attempted to facilitate the movement of internally displaced populations to their cities of origin. The plan to return displaced Iraqis to their areas of origin, which is approved by the Council of Ministers, is meant to support regional recovery, political stability, and security.

In doing so, the Iraqi government has pursued a policy of camp consolidation and closure, which is creating the exact opposite scenario. Camp closures have led to secondary displacement of many IDPs. With that secondary displacement comes a worsening educational crisis that has been brewing for years. This month, according to a December announcement by Minister of Education Ebrahim Namis al-Jibouri, the Iraqi government will close the doors of the last schools for internally displaced students in the Kurdistan region. These school closures will impact an estimated 170,000 internally displaced students in Iraq, contributing to further instability and insecurity for these children.

In 2020, I wrote my dissertation on IDP access to education in Iraq. As part of that work, I interviewed IDP families to understand how their access to education was impacted by displacement. Primary barriers IDPs face in accessing education include missing documentation required to enroll in schooling, mismatch between age and grade level due to interruptions, poverty leading to participation in child labor, and lack of educational infrastructure. Unfortunately, there has been little progress in the past 3 years, particularly as the impacts of COVID-19 and rising inflation compound financial insecurity.

Six million Iraqis were displaced due to Daesh occupation and violence between 2014-2017, and although many have returned to their communities, there remain approximately 1.2 million IDPs across the country. However, progress remains at a standstill in recent years. In 2020, there were 1.3 million IDPs, suggesting the needle is not moving on returns in the last 3 years. The currently displaced population is highly vulnerable, many of whom saw a secondary displacement due to camp closures, and face significant challenges in accessing education. According to REACH’s 2023 survey, 98% of those remaining in Iraq’s 26 formal displacement camps do not plan on returning to their home cities, due to their lack of financial resources and concerns over security.

The closure of IDP schools will severely disrupt students’ educational access. Many of these students have already endured multiple disruptions to their education, from their period of displacement, to COVID-related closures, and now the latest school closures.

IDPs navigate an education system that is near collapse, even for students in secure housing environments. The picture looks bleak across the country, regardless of IDP status. Today, Iraq ranks at the bottom of the region across key metrics. 28% of adolescents and 7% of children are out of school, more than double their regional peers. Among students who stay in school, they learn less than their peers; Iraq’s learning-adjusted years of schooling rate is 4 versus the regional average of 7.25.

For IDPs, the numbers paint an even bleaker picture. Out-of-school rates are even higher for IDP youth. In 2020, approximately 25% of IDP children in Iraq were out of school. Some areas fare worse than others. In a survey conducted by the International Rescue Committee in East Mosul, nearly half the school-age population is out of school. Child labor was cited as a top reason for the high out-of-school rate.

Where do we go from here? Iraq has experienced protracted conflicts and emergencies in its recent history. The challenges IDPs face in accessing schooling are extreme, but they are situated in a broken system impacting the entire country. Years of disinvestment in education in the face of these crises (during the Iraq-Iran War (1980-88), Gulf War (1991), UN-imposed sanction (1991-2003), American occupation (2003-11), ISIS War (2014-17)) has led to the near-collapse of the system. It may surprise some to hear that just a few decades ago, Iraq’s education system was considered one of the best in the Middle East. Fixing the education system requires sustained investment and reform tackling root causes of the challenges, rather than band-aid solutions.

For example, the closure of IDP schools would not be alarming if it were truly a sign that these temporary schools were no longer needed. Rather, it is being done hastily without a path for student re-integration. For example, many students who are still attending IDP schools do so because they cannot enroll in other public schools. These children often are missing documents such as their national identity cards or birth certificates, which are required to enroll in school. By closing the schools, these children will likely lose their opportunity to pursue an education.

The implications of this challenge are far-reaching, and the learning crisis is far from over. If the current generation is robbed of its right to learn, how will they build a better Iraq?

This essay is part of a special series – Iraq after 2003: The Voices of Iraqi Women

Mariam Hassoun

Mariam Hassoun is a writer, education consultant, and founder of Baraka English School. She researches how education can be used to reconstruct post-conflict systems and countries and education as a human right in emergencies. She specializes in education in Iraq.