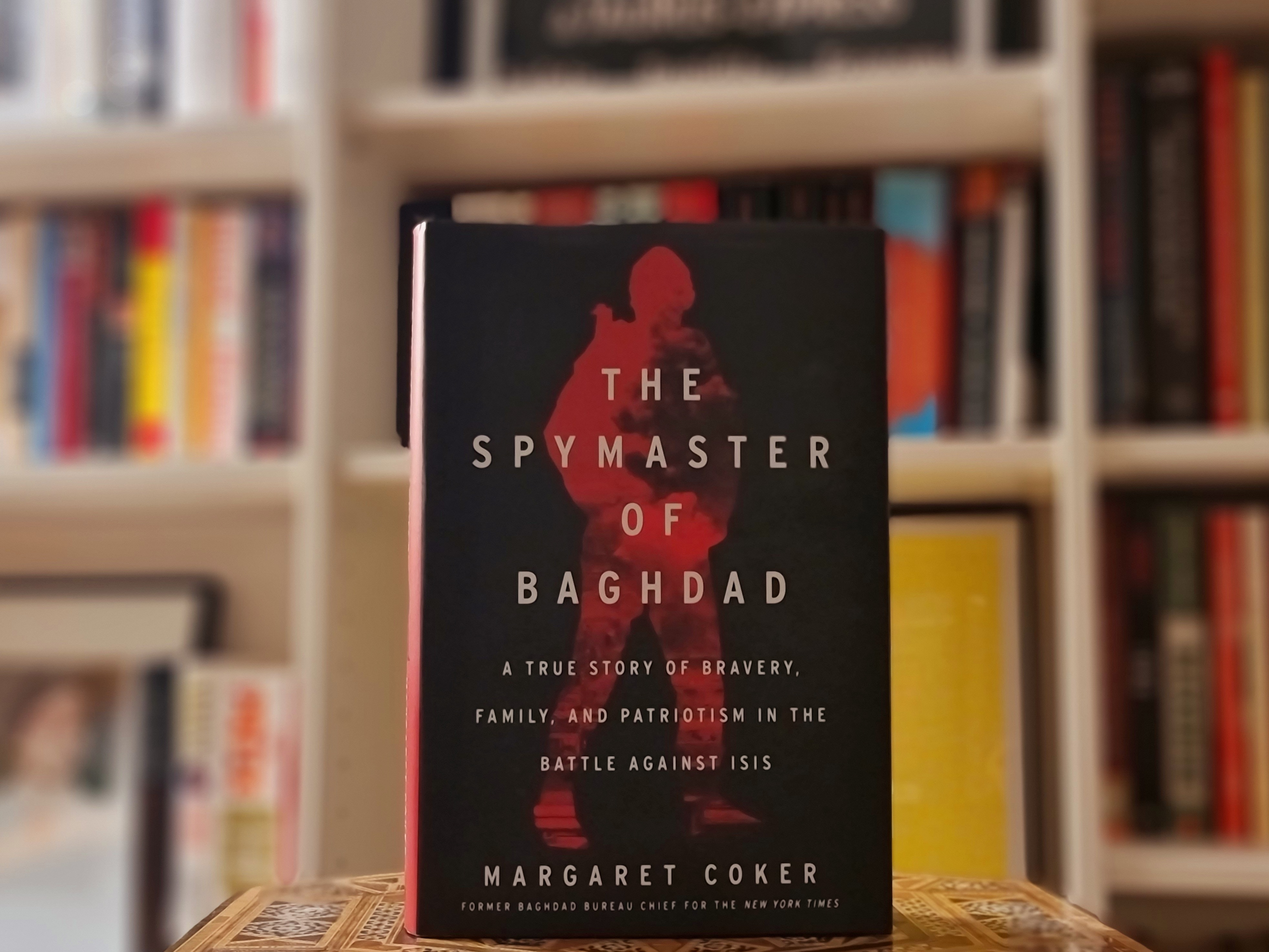

If I were to draw inspiration from the writing style of the last 300 or so pages I read, I would say that my feelings towards this book are as extreme as the Baghdad weather. On the one hand, the story of heroes like Harith Al-Sudani needs to be told, particularly at a time when Iraqis seem to be written out of the history of the fight against Da’ish. The Spymaster of Baghdad does a good job in taking the reader through the history of the Falcon Cell intelligence unit, how and why it was conceived and the successes it has enjoyed which, owing to the nature of the job it does, are not necessarily common knowledge. The book focuses on four main characters: Abu Ali Al-Basri, the Falcons’ chief; Harith and Munaf Al-Sudani, two brothers from Sadr City whose exploits against Da’ish form the bulk of the story; and Abrar Al-Kubaisi, a young Baghdadi woman who becomes radicalised and joins Da’ish with the ambition of bolstering their chemical weapons capabilities. The Spymaster of Baghdad succeeds in telling these stories. It is a compelling page-turner that memorialises the unimaginable bravery of Harith, the Iraqi spy who saved hundreds of lives.

But this book is also terribly flawed. Whole sections are composed almost entirely of clichés (“…Ayman al-Zarqawi [sic] hoped would reignite the blood-soaked theological battles that had raged in Iraq twelve hundred years earlier”) or orientalist tropes, for example on the corruption of Iraqis (“He was as clean as an Iraqi man could be”). Some of the author’s characterisations are so skewed that they leave one wondering how she could have spent so long reporting in the country — we all know that Baghdadis would not consider a twenty year old woman to be “already near the upper limit for eligible bachelors to consider”.

The author is also unforgiving to context, and instead seems to attribute behaviour to an innate Iraqi-ness, rather than to circumstance. At one point in the book, families are stuck for hours on a highway that was shut suddenly by the U.S. army, causing drivers to try different options. To the author, this was not a natural reaction to being stuck, but rather a part of a wider character flaw in Iraqis as a whole: “As usual, Iraqis considered lane lines to be mere traffic suggestions, and impatient drivers pushed into every available crevice, anxious to advance even one foot in interminable delay”.

Another character flaw according to the author, found this time in Iraqi journalists specifically, is that they cannot think critically, and “as usual…[they] had accepted what authorities had told them”. This criticism, from the former New York Times Baghdad Bureau Chief is particularly tone-deaf and ironic, given that it was an alumna of her organisation, Judith Miller, who played an integral part selling untruths about Iraq to the public in the run up to the 2003 war. The author would be advised, in fact, to read Miller’s own defence of her actions before she casts aspersions on all Iraqi journalists: “My job isn’t to assess the government’s information and be an independent intelligence analyst myself. My job is to tell readers of The New York Times what the government thought about Iraq’s arsenal”.

Apart from the tone, the book is problematic in its revision of Iraq’s recent history. The chronology of public sentiment is off; bodies did not “replace ducks” in the Tigris in 2004, when those that were inclined to violence trained their guns at U.S. troops rather than each other. Her account of a Da’ish terrorist, Abrar, who had left her family in Baghdad for Mosul (through Syria and Turkey) with the ambition of weaponising ricin and using it to poison Baghdad’s water supply, bordered on romanticisation. Abrar left her family to join the caliphate to kill people, why then would she be surprised that her fellow terrorist was “only interested in the maximum number of deaths a ricin attack could cause” rather than the “glories of scientific achievement”? The framing of Abrar’s motivations in the book swing incoherently between a desire to return to the heyday of Islamic scientific excellence, and a desire to indiscriminately kill as many heretics are possible. Apart from the inconsistency, Abrar’s whole story does not fit easily with that of the three other protagonists in this book, and leaves the reader wondering why it was included in the first place.

Perhaps the most telling error comes later in the book, when the main protagonist “positioned his father’s carpet on the floor facing east, in the direction of Mecca”. Mecca, of course, lies west of Iraq. That one slip may explain a lot: this book reads like it was written for Hollywood.

But herein lies the paradox. While the tone and language of this book were grating to this Iraqi, the overall purpose of the book is the opposite. The author says from the outset that her aim in this book is to “recalibrate Iraq’s history away from one that until now has centered on the Americans’ sin, suffering, and victories, and to illuminate the admirable role that Iraqis have played and the sacrifices they have made on behalf of their country and the world in the war on terror”. These are noble aims, and a fair assessment of the book would account for the fact that the author did succeed in shining a bright light on the heroism of Iraqis that has too often gone unnoticed. Iraqis have not been able to chronicle and transmit our contemporary history to a wider audience. This book, despite its faults, at least immortalises the sacrifices of Harith Al-Sudani.

Ali Al-Saffar

Ali Al-Saffar is Iraqi-British who works on energy and economics of the Middle East and North Africa region. He is an avid reader of books concerning Iraq.