(Council of Representatives. Reuters)

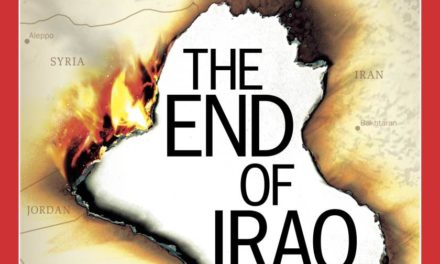

The democratic system in Iraq has survived several existential threats, beginning with the sectarian violence of 2006, the emergence of ISIS, and other constitutional and political crises. With each crisis, analysts are quick to predict the end of Iraq, but the post-2003 democratic system has demonstrated its resilience over and over again.

Scholars have attributed democratic breakdown or survival either to agency (elites), or to structural factors consisting of three main variations: first, the internal dynamics, such as the level of economic development, the size of the working class, and the degree of dependence on primary exports; second, the institutional design; third, international conditions.

A recent quantitative study that looked at democratic survival and breakdown in Latin America from 1945 to 2010 found that neither the level of development nor economic performance directly shaped the prospects of democratic survival. Rather, the normative preferences of elites for democracy and their policy preferences, as well as the regional political environment, explained democratic breakdown and survival.

Elites are defined as “persons who are able, by virtue of their authoritative positions in powerful organizations and movements of whatever kind, to affect the national political outcome regularly and substantially”. Higley and Burton emphasized elite disunity and elite consensus in democratic transition and breakdown.

Iraqi political elites are divided over many issues (future of PMU, foreign policy, distribution of wealth), therefore, it is safe to say that political disunity is the norm in Iraqi politics. This may appear in the process of government formation, which usually takes a long and murky road. However, the majority of political elites rally behind democracy once it is under threat, as evident in the response to several crises, such as ISIS, the Kurdish referendum, and electoral fraud. For example, political elites quickly mobilized around the judiciary to ensure the transparency of elections, after a governmental committee confirmed such claims, and parliament voted for suspending IHEC commissioners and delegate their powers to the judiciary. Therefore, elites have resorted to the constitution and federal institutions to respond to crises that could threaten the democratic system itself. It reflects a temporary consensus that rises with every existential crisis. Such consensus could be explained by their desire to preserve the status quo, as their own survival is deeply connected to the preservation of the existing system.

This does not deny the fact that some political elites are working on reversing the democratic transition to achieve or consolidate ethnic and sectarian gains. Otherwise, these crises would not emerge in the first place. However, there are political, economic, and social drivers for moderation that shape elite behavior, namely the institutional designs of the political system, the domestic economic interdependence, and the support for democracy by influential social power centers.

The institutional design of Iraq, based on a parliamentary system and proportional representation, pushes elites to keep their channels open. The electoral system ensures that each party gets seats in proportion to their share of votes. Also, the absence of a formal threshold, the relatively large district magnitude, and the option of fielding numerous candidates for each electoral district enable tens of political parties to win sizeable shares of parliamentary seats. Furthermore, the Federal Supreme Court ruling that defines the “largest bloc” as the one submitted on the first session of the newly elected parliament – rather than the electoral list that won the most seats – requires building a coalition of winners to form a government.

Previous government formation negotiations have led to unity governments, where all winners participate in the government by distributing ministerial posts based on informal quotas. Despite the fact that this scenario is still probable, the rhetoric of political elites in the 2018 election emphasized the idea of a majoritarian government. Even if this idea is implemented, support from two-thirds of parliament (approximately 219) is required, given that elites traditionally reach a grand bargain over the three main positions (parliament speaker, president, and prime minister) and the position of president requires a two-thirds majority. Furthermore, a majoritarian government is not limited to a numeric majority, as it needs to incorporate all the different Iraqi ethno-sectarian identities. Therefore, these institutional rules and norms drive most elites to take conciliatory positions in order to engage in negotiations with their rivals in the process of government formation.

Iraq’s dependency on oil and the concentration of oil in the southern parts of Iraq has led to economic interdependence, where northern and western parts of Iraq need access to the resources of the south to run their local economies, while the southern parts need access to trade routes from the north and west. Wealth distribution is decided annually based on a political understanding that is reflected in the annual budget, suggested by the government and voted on by the Council of Representatives with a simple majority, rather than being pre-determined by specific rules. For example, when the KRG started to export oil without Baghdad’s approval, they did not receive their share of the federal budget, and when they decided to pursue a much more radical step, namely holding the independence referendum, they were quickly isolated from the Iraqi economy and were forced to accept federal authority to regain their access. Therefore, it seems that elite sanctions mitigate against pursuing radical policy options.

Social dynamics is another driver for moderation, as power-centers that enjoy sizeable influence over Iraqis advocate for the preservation of democracy in Iraq. An obvious example is the religious establishment represented by Grand Ayatollah Sistani who demonstrated on several occasions the importance of maintaining the democratic nature of the political system by calling on people to participate in elections, pressuring policy makers to respond to popular demands, and promoting democratic values, such as the peaceful transfer of power and coexistence. This support for democracy is not limited to Najaf, but extends to academics, business leaders, and other social groups. This does not deny that these social groups have reservations over the conduct of politics in Iraq, but they call for reform rather than radical changes to the system.

To sum up, elite preferences and policy options seems to be shaped by political, economic, and social drivers for moderation. However, paradoxically, these drivers also hold the seeds for destabilizing democracy, as the institutional design has led to weak governance; dependence on oil leads to a fragile economy; and different social groups frequently mobilize into angry demonstrations to voice their dissatisfaction with the status quo. This highlights the fragile balance, where elites are incentivized to preserve democracy by political, economic, and social factors, but these factors lead to adverse consequences that need to be addressed through incrementally reforming institutional designs, diversifying the economy, and meeting the basic needs and expectations of the general public.

Hashim Al-Rikabi

Hashim Al-Rikabi is a researcher at Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies in Baghdad where he focusses on institutional reform and rule of law. He holds a Master’s in Political Science from Western Illinois University.