Iraq’s parliamentary democracy has suffered from the absence of a parliamentary opposition since its inception in 2005. All political factions that won previous elections have formed coalition governments that are based on sectarian quotas because no one was willing to play the role of opposition. The immediate consequence was endemic corruption as each faction defends its executive nominees, even if they are corrupt or incompetent. But the differences among current political contestants in terms of programs, regional and international backing, and personalities indicate the possibility of having a parliamentary opposition in post-ISIS Iraq.

The literature shows several advantages to having a formal opposition, such as improving government performance, enhancing legitimacy, channeling disagreements and disputes through parliament, and preparing the opposition to govern. The Iraqi parliament witnessed several short-lived parliamentary oppositions that are formed by parties who are part of the government too, therefore, the norm was the absence of an effective parliamentary opposition. This could be attributed to several factors, such as the lack of trust among political factions, fear of losing resources necessary to operate and expand their patronage networks, fear of prosecution, and more importantly fear of demise or irrelevance. Even though some of these factors remain relevant today, the current political environment is shifting away from including all political contestants in the process of government formation following the upcoming parliamentary election in May 2018.

Current political contestants are polarized around several crucial issues, which could be classified into; First, the future of Popular Mobilization Forces, whether it should be completely disbanded, integrated into the Iraqi Army, or institutionalized. Second, the response to regional rivalries is another source of polarization. The power struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran polarized the region into three camps; neutral, pro-Saudi, and pro-Iran. These trends have resonance among political contestants, as some push for aligning with one camp or another and others insist on maintaining a neutral position. Third, the economy is another source of polarization, as the political class has taken opposing sides on issues of privatization, taxation, and streamlining bureaucracy. While the incumbent government supports these measures, several parties voiced their opposition and mobilized their bases to protest such measures. The differences among political elites do not end here but extend to other issues, such as reconstruction (whether to be limited to liberated areas or extended to others), decentralization (and the extent to which it should be implemented), and even the nature of the electoral and political system. Thus, the political class has taken extremely opposing sides on issues of security, economy and regional rivalry.

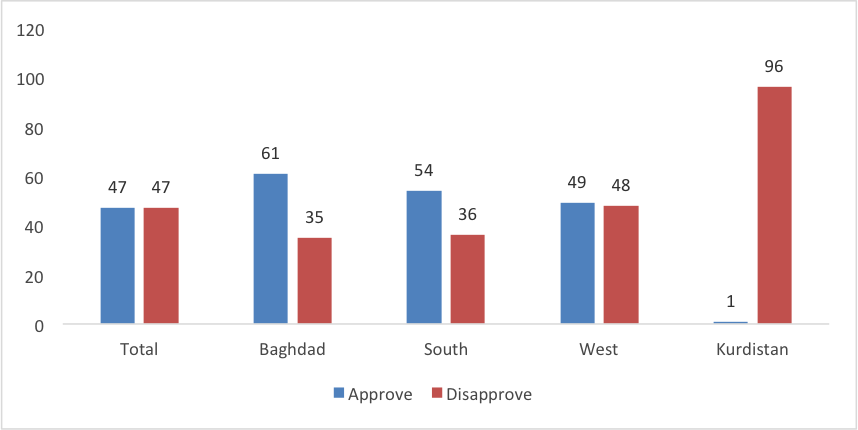

Political polarization cannot be explained based on sectarian and ethnic identities alone since intra-communal differences between political factions also exist. This polarization is not limited to the political class, but even popular bases are polarized around these issues, for example, a survey found that 40% of Iraqis support PMU integration into the Army, while 23% support its institutionalization, in contrast to 16% who favor disbanding the PMU. Also, there is cross-sectarian polarization on the issue of PMUs entering politics, as appears in Chart I.

Chart 1. Approval of PMU entering politics. Source: National Democratic Institute

Such a polarized political scene might explain the rationale behind the alternatives that have been advocated by some prominent political factions to escape the quota system, such as a majoritarian government. While some political contestants restrict the latter alternative to a numeric majority, most advocate for a majoritarian government that excludes some winners while maintaining the inclusion of all sectarian and ethnic groups in government formation.

Given political realities on the ground, it is difficult to have a formal opposition with a shadow government as in the United Kingdom,[1] but it is likely to have a small opposition, which will be composed of varied (religiously and ethnically) political contestants and driven by a rational calculation to form one front. This will help the political system shift away from identity-based politics into issues-based politics. Also, the Iraqi parliament rules of procedure allocate crucial powers to committees, which are relatively small (7 – 17 members), permanent, and specialized in particular policy areas. This provides the opposition with a window of opportunity to influence the process of policy making, notwithstanding the option of mobilizing on the streets to pressure the governing coalition.

To sum up, differences among current political contestants are not rhetorical anymore. Therefore, it is possible to see an inclusive majoritarian government emerge after the May elections, where some factions are left to play the role of parliamentary opposition. There are several institutional opportunities to exercise this role and it has the potential to enrich Iraq’s democratic experience.

[4] The Shadow Cabinet consists of members from the main opposition party in the House of Commons and Lords, currently the Labour Party. Its role is to examine the work of each government department and develop alternative policies in their specific areas. For further information see https://goo.gl/hiQzqZ

Hashim Al-Rikabi

Hashim Al-Rikabi is a researcher at Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies in Baghdad where he focusses on institutional reform and rule of law. He holds a Master’s in Political Science from Western Illinois University.