I’m frequently asked to write security assessments of Baghdad, to gauge what the risks are and what the associated political fallout could be. Only 10 days ago I was asked for my thoughts on Baghdad security: would a Daesh bombing campaign continue after Fallujah was liberated (yes because Daesh has always used them to project strength), how likely would an attack occur around Eid (very likely as Daesh targets crowded areas and especially increases attacks in Ramadhan), can they penetrate inner Baghdad areas such as Karrada (yes because these bombings are planned and have assistance to get them through checkpoints), and would there be a breakout of violence in response to such an attack (unlikely as there is a war being fought but popular anger would certainly be high). I move freely around Baghdad and the provinces, but I have always minimised my time in crowded areas because they have been so frequently targeted over the years. Relatives, friends or someone I know have been killed or injured in every year since 2003, and I expect this trend to continue for a while yet. The Karrada bombing did not come out of the blue, many people like myself who are keen Iraq observers were expecting something like this to happen because Daesh wants the fallout to serve its causes and because the security establishment remains weak in Iraq. Terrorism is certainly the cause, but incompetence and corruption play a part in allowing it to occur.

On Saturday evening I was with friends in the western end of the Karrada area, near the Babylon Hotel, watching the Germany-Italy football match. It was a very warm night and we were sat outside in a popular restaurant cheering for Italy to win but expecting Germany to. At around midnight the match was forced into extra time and then a penalty shootout. Around me every one was watching nervously as the game reached its conclusion. At 12.50am it was the Germans who came out victorious and we all felt sorry for the Italians who never seem to do well at penalty kicks. As we were still discussing the result we suddenly felt the shockwave of a bomb and the loud sound of an explosion accompanying it, meaning it was nearby. Living in Baghdad means you learn to differentiate between a car bomb, a truck bomb, a Grad or Katyusha rocket, a mortar, a grenade, an improvised landmine or IED, a missile, or just a plain sound bomb. This sounded like it was a car bomb, not big enough for any more than that, perhaps 2-3 kilometres away, likely to kill 10 people and not out of the ordinary for a city that has seen hundreds of such incidents over the past decade. We all reached for our phones to see the initial reports on social media and within 5 minutes we saw messages that it was in Karrada, next to Hadi Center mall. We all said it would be bad because we knew how crowded that area gets at night. Next we got images of a raging fire and then we saw fire trucks and ambulances speeding past us down the Karrada Dakhil road towards the explosion site. The mood changed and nobody was talking about the football anymore, and then phones started ringing, with wives, mothers, sisters, daughters calling their family members to ask that they go back home. Suddenly the restaurant started to thin out, and by 2am I was pretty much the last one there (unthinkable on a usual night). I drove down Karrada Dakhil, and could see the orange glow from the flames in the night sky and the screams of sirens and people running. Panic was the overwhelming feeling that gripped this area and with more emergency vehicles cramming into the road I decided to move away and turned onto Karrada Kharij and back home. On Facebook and Twitter the photos posted were showing the mall engulfed in flames. The death toll began to creep past 15 and this started to look like a worse attack than I expected. At 4am I went to sleep thinking the situation would settle by late morning and we would get a death toll in the mid 30s.

That’s what happens in Iraq, deaths become just statistics and the frequency of attacks means the shock doesn’t register as it would elsewhere or that you have enough time to feel sad or grieve. I was near the Karrada area on 2 May 2015 when a twin bombing killed Ammar al-Shahbander, a friend of so many Iraqis and foreigners alike and one of the most energetic and optimistic people you could meet in Baghdad. He was killed, along with 16 others, very close to Hadi mall and on a similarly busy evening. Tragic but one of so many attacks, and I remembered Ammar while having an intense feeling of déjà vu.

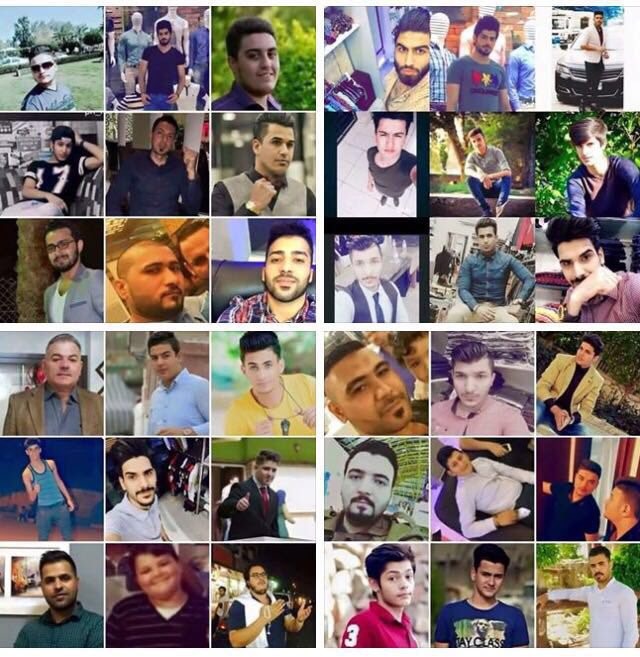

My phone began to ring and buzz with calls and message alerts at 7am. The death toll had reached 65, I had several emails asking for an update and messages from friends and relatives checking on me, and news that PM Abadi was at the site of the bombing. I was shocked at the death toll, the explosion didn’t seem powerful enough for such a figure, perhaps there was something else that was not yet reported. At 8.30am I drove to work to expecting the usual rush hour traffic but the streets were strangely quiet, as if it was under curfew. The mood was depressing and the smell of fire hung over the city. Every person you looked in the face seemed in a state between shock and sadness, and you couldn’t tell if they were directly affected by the bombing or not. In a meeting at 9am some early details came to light and the number of dead surged past 80. Flames were still being put out, the basement of the mall was still too hot to enter, families were frantically searching through the ashes for their missing ones. From 10am to midday, in between calls, messages, and meetings, I watched on local TV and social media the death toll go up: 100, 110, 115, 120, 130, 140. A feeling of anger and sadness gripped me but the numbness from nearly identical experiences meant my emotions were in check. Then something changed to make the situation more real, to change it from a news event to a personal tragedy. I was told that a friend of mine, Ahmad Dhia, was missing and he was in the area at the time of the bombing, with his two brothers-in-law shopping for Eid presents for their families. I asked some of his other friends for an update, not wanting to call his family who had been up all night trying to get hold of him. His phone was last active at 12.55am, after that it could not be reached. At 1pm his work colleagues had found his car about 50 metres from the mall, but couldn’t get into the mall as bodies and charred corpses were still being pulled out slowly. His family had spread out across the city’s hospitals searching for him and a few friends were sent to the morgue to stay on watch in case his body showed up there. I’m not sure what I can do to help so I post on Twitter the news that he is missing with a faint hope that someone has some information, maybe they saw him injured in a hospital or he was seen earlier in the morning near the bomb site. By 4pm there was still no word and I had declined several media interviews because I didn’t feel up to commenting in my usual detached manner while Ahmad was still missing. A sense of dread had set in, your heart tells you to have hope and gives you several reasons why you haven’t heard from him yet, but your brain is telling you to be realistic, you know what has happened but do not want to accept it and any moment now it will be confirmed. I drive towards the bomb site but can’t get close enough to be of any use and while standing looking at the blackened sidewalk and gutted mall someone next to me who looks like he has been shovelling through ash the whole day stares at me and bluntly states ‘he is dead, whoever it is you are looking for is dead, if he hasn’t showed up this morning then just accept it’. It feels like a punch in the stomach, you want to respond or lash out but can’t get the words out because the wind is knocked out of you. I walk away because there is nothing to see except death and destruction, and this is a place where hope does not exist, extinguished by flames that have consumed so many young people, and despair has taken hold, something I don’t want to feel right now. At 6pm a message arrives: Ahmad’s burned body was pulled out from the basement. My brain has been trying to prepare me for this but it still hurts as if it is completely unexpected. I’m not sure what to do or how to express what I feel, I just sit and stare at the wall for a bit. I open Ahmad’s Facebook page, I want to see photos of him smiling, to remember him as a wonderful young man, not to think of his burned body. I tear up as I flick through the photos, he was going to achieve so much, he should not be dead.

Ahmad was one of a new generation of well-educated Iraqis who hoped to turn the country around. He worked at the Agriculture Commission which coordinated with several ministries to improve Iraq’s agriculture sector. Ahmad was always writing about ways to enhance modern farming, to increase crop yields, to better manage water resources, to sustainably develop livestock, and every weekend would spend a day at some farm or factory in the provinces where work was taking place to do just that. He wrote a paper last year for us at Bayan Center on sustainable development of agriculture and was working on a paper on food security and crop yields. He was Abu Yusif to his friends and was an optimist who had an infectious energy, totally convinced that our country’s future would be better than its past.

As night falls I continue to decline news interviews, not sure what I would actually say when live on air, probably afraid that I wouldn’t seem calm and dignified, not at all like an analyst who has commented on dozens of such events in the past. On TV I see a crowd has gathered to light candles at the bomb site and some to protest against Daesh and the government, and a mixture of grieving, defiance, and anger is on display as hundreds of people gather in Karrada. A friend calls me from the scene to say that they are using their phones as flashlights because bodies are still being pulled out from the mall. He says the ashes are smouldering and that several people are still missing, including Ahmad’s two brothers-in-law. Over 80 charred corpses are yet to be identified and he thinks the death toll will easily be over 200. This last bit puzzles me, how could a car bomb (SVBIED in this instance to use the analyst parlance) have killed so many, there wasn’t even the usual crater in the road or blast damage to the buildings. Then I remember the details from earlier in the day and realise that it was the fire that killed all those people, the car bomb killed far less.

The Hadi mall was designed, as the vast majority of buildings in Iraq, with no fire safety in mind. There were no emergency exits, the door to the roof was welded shut to prevent the entry of burglars and no sprinklers were in place to assist with putting out fires. There may have been some fire extinguishers but I doubt it. The only way in and out of the building was through the single front entrance. The entire building was clad in plastic based panels, even more combustible than the aluminium based ones blamed for large fires in Dubai hotels this year. Fire safety inspections are rare and weak, and the mall was full of stores with flammable goods with little quality controls. In front of the mall the sidewalk was packed with vendors selling cheap clothes on the ground, perfect material for fires to consume. Next to them were mobile stalls selling falafel and fast food, with deep fryers and several gas canisters underneath. To the side were hundreds of crushed cardboard boxes and discarded packaging ready to be collected by the cleaners in the morning. In all, it was everything needed for an inferno, and the explosion killed a small number of people instantly but the subsequent fire that spread quickly trapped people in the mall and burned them alive. Bodies that looked like they survived the fire were killed by smoke inhalation. In the basement several bodies were found huddled close together, a desperate attempt to protect each other in the final moments. One father’s burned corpse was found shielding his daughter’s. A scene of unimaginable horror, these people died while screaming for help as the flames consumed them. The nearest fire station is at Uqba ibn Nafi Square, too far away to respond quickly (Karrada should have its own) and when they did the water they carried in their fire engines ran out after a short while. One person survived miraculously by jumping into a chest freezer and was rescued before it had completely melted but that was the only such story I’ve heard. Inquiries and inquests rarely lead to results but I fear if the lessons are not learned from the Karrada fire then such disasters could easily occur again.

On Monday the numbers had now become records, the worst attack in Baghdad since 2003 (Only the Speicher massacre and the Imams Bridge stampede had a higher single incident casualty toll). The recriminations are underway, politicians using the tragedy for score settling or to outdo each other in their condemnations and even sectarian innuendo. People are disgusted at the entire ruling system in Iraq, blaming them as much as Daesh. Perhaps that is the biggest change I’ve seen over the years in such attacks, a paradigm shift where the first point of responsibility is the government rather than the terrorists who conducted the attack. Emotions are raw the whole day as images of the victims are shared widely and then their stories, most of them young people, some recent graduates, some working in clothes stalls to earn a living, all of them with people who loved them dearly. The burials begin and Ahmad’s body is interred at Wadi al-Salam in Najaf by his parents and relatives, but his two sisters remain in Baghdad to continue looking for their husbands’ bodies among the ashes and in the morgue.

The Karrada area has been targeted many times over the past decade, and each time there is a call for better protection from bombings but that never results in much change. Around 18 months ago security in the capital had improved and the checkpoint leading into Karrada Dakhil down from Kahramana Square was removed to improve traffic flow. Several small side streets were also opened up having been closed since 2004, and the Baghdad curfew was lifted which encouraged people to stay out late. After the May 2015 bombing the checkpoint was reinstalled but the inherent security risk persisted; cars could easily get into one of the busiest thoroughfares in Baghdad without being searched or checked and park up next shops and cafes filled with hundreds of people in a compact area. On Saturday the intelligence services had received a tip off that a bombing was expected that night and so just after 9pm the checkpoint was closed and cars turned back. For some unknown reason it was briefly reopened around midnight before being closed again. Dozens of cars were allowed into the area and that is when the terrorist made his way in.

Daesh claimed responsibility for the attack, carried out by ‘Abu Maha al-Iraqi’ against a gathering of ‘rafidhi apostates’ a derogatory term for Shia Muslims. That’s what Daesh does, it sets itself up as a Sunni group defending Sunnis by killing Shias because they are Shia, hoping to incite a reaction and a spiral into endless violence. Daesh bombs cannot distinguish between Shia and Sunni and that is why several Sunnis were killed in the bombing, but the message they put out is consistent and clear; they aim to kill Shia Muslims because they are Shia. If any Sunnis are killed in such attacks then that is incidental and not planned, and when Sunnis are targeted it is because they have betrayed their people rather than just for being Sunni. Such sectarian framing is difficult to get away from in a region burning up in sectarian proxy wars and Iraq is at the front line of these wars. It is a trap that many Iraqis and Arabs fall into and I was appalled to read such reactions on social media and even on TV which encouraged accepting the sectarian narrative of such events and the necessary sectarian reply to them. I don’t spend much energy discussing this issue and I don’t intend to here, but we have a societal problem in the Middle East that renders us highly susceptible to sectarian discourse. Education is part of the problem as are the scholars, media and politicians, but it is also the fear that terrorism has sown among communities that leads to sectarian violence (in the words of Yoda: Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Angers leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering). This is exactly what I can see after Saturday’s bombing, fear that more lives will be lost, fear of the other that they will respond, anger at the other, anger at not doing enough to stop it and that extreme measures are required, hate of the other of what they have done and what they will do, the wish to impart suffering on the other so that they will desist.

Daesh is the culprit and the killer, it proudly boasts of its responsibility and so it is to be blamed for what happened. However, anger is also rightly directed at the political and security systems because they bear responsibility for the failings that allow Daesh to conduct such attacks. Corruption is endemic and systemic in Iraq, it is what allows terrorism to strike successfully and this is what happened on Saturday night. Somebody in the security services allowed the bomber to get into Karrada, somebody knew about it and was paid well to keep quiet, and somebody turned a blind eye to such failings time and again. Minor checkpoints are an absolute waste in the way they are operated at the moment, several of them are even a means to extort money from civilians for non-existent traffic offences. My criticisms of these checkpoints are:

- They do not prevent the free movement of terrorists and car bombs because they do not stop or search vehicles nowhere near enough to catch anyone, they simply wave everyone through

- They are static and predictable and can be easily avoided with enough planning

- There are no sniffer dogs or x-ray vehicles to check for weapons and bombs

- They cause a build-up of traffic that becomes a target in itself

- The police manning these checkpoints are lazy, on their phones or chatting with each other or not interested in stopping anyone

- There is no intelligence provided to make searches more effective, the police do not know what they are supposed to be looking for and it is a needle in a haystack effort

- The officers manning the checkpoints can be tricked, intimidated or bribed into letting vehicles through

- Fake number plates and ID cards are easily available and no mechanism exists to check these at the minor checkpoints

- They build reliance and overconfidence that they will prevent bombings, especially when using those pathetic fake bomb detectors

- They take away manpower and resources that could be better put to use elsewhere

I would much rather these internal checkpoints are removed and replaced with other security measures that improve city wide security as opposed to focusing on individual neighbourhoods. Some suggestions:

- Deploy moving, rolling and random checkpoints equipped with sniffer dogs that can quickly check vehicles

- Mobile police patrols on foot that can observe behaviour and movements from within crowds

- CCTV at all major roads to monitor vehicles being parked and suspicious activity

- Robust checkpoints at city entry points that search and x-ray every vehicle

- Preventing cars being parked next to crowded areas, using parking garages instead

- Continuous aerial surveillance to track suspicious vehicles and people that move across neighbourhoods without alerting them

- A thorough clean out and retraining of the police force

- Deployment of plain clothes intelligence agents from inter-agency departments near crowded areas and mosques, etc to discreetly observe movements

- Encouraging the formation of a neighbourhood watch that can alert to the presence of suspicious vehicles and packages

But there is much more to it than that, in order to achieve better security the entire state needs to be fixed. The politics are broken, the economy is struggling, the justice system needs improving, trust from the people needs to be regained. While these issues are not addressed then security will continue to suffer. Daesh will be defeated on the battlefield but our weaknesses as a nation and state will persist unless radical change occurs. I cannot foresee a better future without us learning from the past, we cannot fight our way to peace and prosperity nor expect good intentions from our friends and enemies. We must do better as Iraqis, from the individual citizen to the head of state, the past 13 years have shown that true dedication to the country is rare and faith has disappeared. The Karrada attack highlights the evil of Daesh and also the failings of Iraqis. The bitter truth is that Daesh is to blame but there is a tiny bit of Daesh in all Iraqis/Arabs/Muslims, waiting for the provocation to set us off against each other. I’ve often mentioned that the ideology of Daesh is what must be addressed and the danger of extremist teachings must be tackled but Daesh is not completely foreign and it has supporters inside Iraq as well as outside. The reality is that Shias and Sunnis must live side-by-side in Iraq and nothing can change that. Peace can only be reached if violence is rejected as a means of achieving goals, and no side is capable of wiping out the other but that message has still not sunk in.

I’ll end my comments here as I started, with an assessment of the security situation. Will there be reprisals (probably not as the scale of the disaster has brought some unity), will Daesh continue with attacks (yes and they will be eager to take advantage of the palpable fear and anger), will this lead to the fall of the government (no but some heads will have to roll in order to show an effort to tackle the security problem).

We lost so many bright and talented people on Saturday night, and we should grieve and remember them in the most fitting manner. Our response as a nation should be to unite, to support our armed forces to prevent the terrorists from winning, to help our communities protect each other, and most of all to not allow fear and hate to consume us. For the politicians this should serve as a wakeup call, they need to stop maximising their political gains at the cost of innocent lives. For the security and intelligence services they need to do better, negligence, incompetence and corruption allowed the Karrada disaster to happen. For religious leaders and paramilitary leaders, please focus your energies on Daesh, do not take advantage of our broken hearts to further sectarian agendas. For our neighbours, please help us by tackling sectarian hate, stop the proxy wars and stop using our country as a means to an end. For the world, please remember Iraq and its people in your prayers, your show of support means a great deal.

This piece was originally published on https://sjiyad.wordpress.com/2016/07/05/the-flames-that-consumed-hope/

Sajad Jiyad

Sajad Jiyad is a researcher on Iraq, Middle Eastern Politics and Islamic Studies. He is working on several projects and publications, and frequently appears in the media.