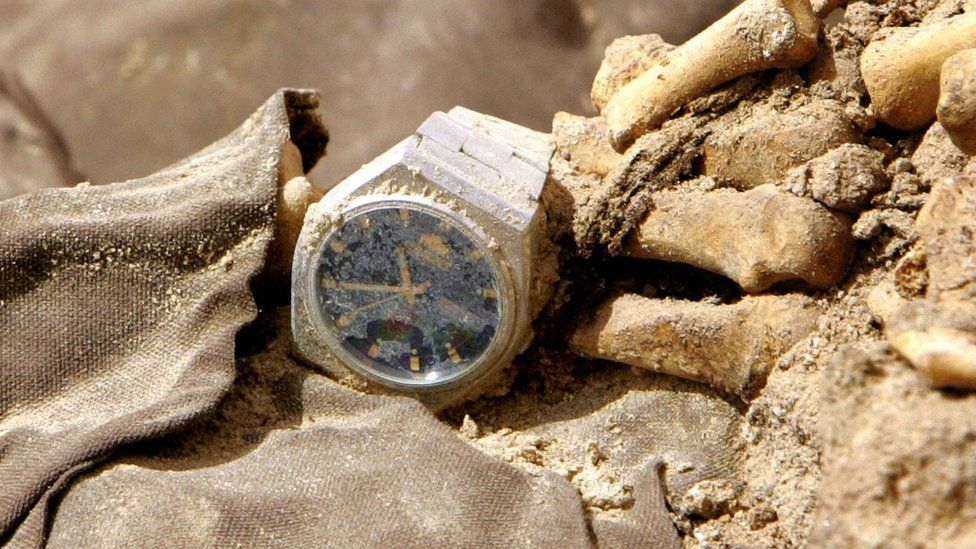

(Watch found on victim in mass grave. Photo: BBC/Getty Images)

As Raghad Hussein, daughter of Saddam Hussein, made appearances on Al Arabiya News last month, individuals expressed their conflicting views on the deceased leader and the Ba’ath Party. There was visible praise from young Iraqi Arabs on social media to the dismay of many older Iraqis. Reasonably, they directed anger at those who expressed approval, but these conversations tended to disregard the motivations behind Ba’ath era nostalgia. It is imperative to understand the causes of authoritarian nostalgia and its potential repercussions on security and intercommunal relations if government inaction allows it to progress.

About 57 percent of Iraq’s population is under 25, meaning most Iraqis were either too young to remember the Ba’ath era vividly or had not been born then. Inevitably, some, including younger Shia Arabs from the neglected and repressed South, do not view the former dictatorship as unfavorable as much as once presumed. The post-2003 authority has instead taken on an adversarial role, despite being primarily composed of parties that opposed Ba’athist rule and some that even supported the United States-led invasion and subsequent toppling of the former regime. The current government’s failures in protecting sovereignty, handling ethno-sectarian tensions, and providing essential services have only deepened public discontent and distrust in the political system, especially among the youth that grew up in the resultant dire conditions.

In turn, Iraqis have arrived at the false conclusion that they must choose between either stability or democracy, with the former being the preferred option at the moment.

Moreover, this phenomenon is not exclusive to the youth either. In recent years, members of older generations have expressed their yearnings for the long-departed monarchy. Although these previous eras were not as stable as assumed –– with frequent revolts under the royalists and subsequent wars under the Ba’athists –– people overlook the past turmoil due to the continuation of violence. They argue that although former regimes restricted freedoms, they at least governed more productively. Adding to this argument, most indicate that state-led repression never ceased, as noted by the violence government forces and suspected militias have perpetrated against protesters and activists since October 2019.

This lack of confidence alone puts Iraq in an unstable position. As most citizens believe elections are incapable of producing systematic change, individuals are inclined to demonstrate more frequently and intensely. The brutal suppression of protesters and hesitation to meet their demands only further this distress. And, eventually, there comes a time when young Iraqis are no longer willing to endure the continuation of the destructive status quo, requiring them to strike back.

Moreover, when these grievances are coupled with resultant authoritarian nostalgia, uncertainty grows. A developing critique of the Tishreen Protest Movement is the lack of centralization and direction. Figures or groups could exploit this perceived fault and widespread uneasiness to heighten support for their political agendas. On a more extreme level, a leader could captivate susceptive crowds by pledging to fill in the power vacuum as their desired strongman. While such a seizure of control is unlikely, the government should not underestimate its possibility. It could risk a resurgence in political violence from several sides, hindering Iraq’s recovery from decades of war.

This authoritarian nostalgia also contributes to the division between Iraqi Arabs and Kurds. Due to regional separation and a widening language gap, contact between the two ethnic groups today is minimal compared to previous decades. This lack of communication exacerbates mutual misunderstanding between Arab and Kurdish communities primarily caused by massacres under the Arab nationalist regime and ongoing regional and federal government disputes.

Although Shia also faced terrors under Saddam Hussein, some Shia Arab youth have no perception of this, due to both nostalgia and the lack of education about the era. By contrast, students in the Kurdistan Region have better access to genocide memorial sites and a school curriculum on the subject, making them more knowledgeable on past persecution against their group. Yet, at the same time, the highly politicized education system has also fostered divisions between Kurdish youth and other ethnic and religious components of Iraq.

Among other factors already responsible for the disconnect, authoritarian nostalgia also plays a detrimental role. As Kurds observe increasing preference for Ba’athists from Arab youth, many of them reasonably develop unfavorable opinions about the group or have their existent prejudices reaffirmed. Recognition and condemnation of injustices are integral to reconciliation, yet the rising occurrence of the contrary ultimately stunts these efforts. Failure to address severed bonds between Iraq’s two largest ethnic components perpetuates this fatal division, leaving the nation weak and overwhelmed by communal conflicts.

Ironically, authoritarian nostalgia supplies the same conditions that encourage its rise – instability, political stagnation, and ethno-sectarian conflict. For Iraq to progress, federal and regional officials must confront the issue and acknowledge their failures that generated it. Although this longing is not justified, it is understandable and will become more prevalent if decision-makers do not address its sources. To start, instead of minimizing protesters as infiltrators or Ba’athists, the government should perhaps address their demands before its negligence plunges the nation into further descent.

Neil Joseph Nakkash

Neil Joseph Nakkash is an undergraduate at the University of Michigan’s Ford School of Public Policy.