Last week Iraq hosted the Arab League Summit for the fourth time in its history. The last time Iraq hosted the summit was in 2012, when the new Iraq was attempting to reintegrate into the regional order, only to be hindered by major security concerns. Regional actors shunned the 2012 summit, later appearing vindicated when Iraq found itself embroiled in a war with ISIS a mere two years later. Nearly eight years after Iraqis defeated ISIS on their territory, Baghdad was keen to show off its hard-earned security, but was met with poor attendance again and bad domestic press. The poor attendance could be attributed to President Trump’s visit to the region, the emergency Arab League meeting held in Cairo weeks prior, and Iraq’s ongoing maritime dispute with Kuwait.

In the last few years, a series of conferences and international events in Iraq have cemented the image of its stability and security among regional actors. In 2019, Iraq’s then Speaker of Parliament Mohammed Al-Halbousi held a parliamentary summit in Baghdad, where five of his six counterparts from neighboring countries attended, including the Saudis. This was the start of many conferences and summits held in the Iraqi capital. These events also served as advertisement for their host. For example, former Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi wanted to leave his mark by hosting the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership, co-hosted with French President Emmanuel Macron. He invited neighbouring states, emphasizing the attendance of heads of states from Gulf countries who were absent at the Arab League Summit in 2012.

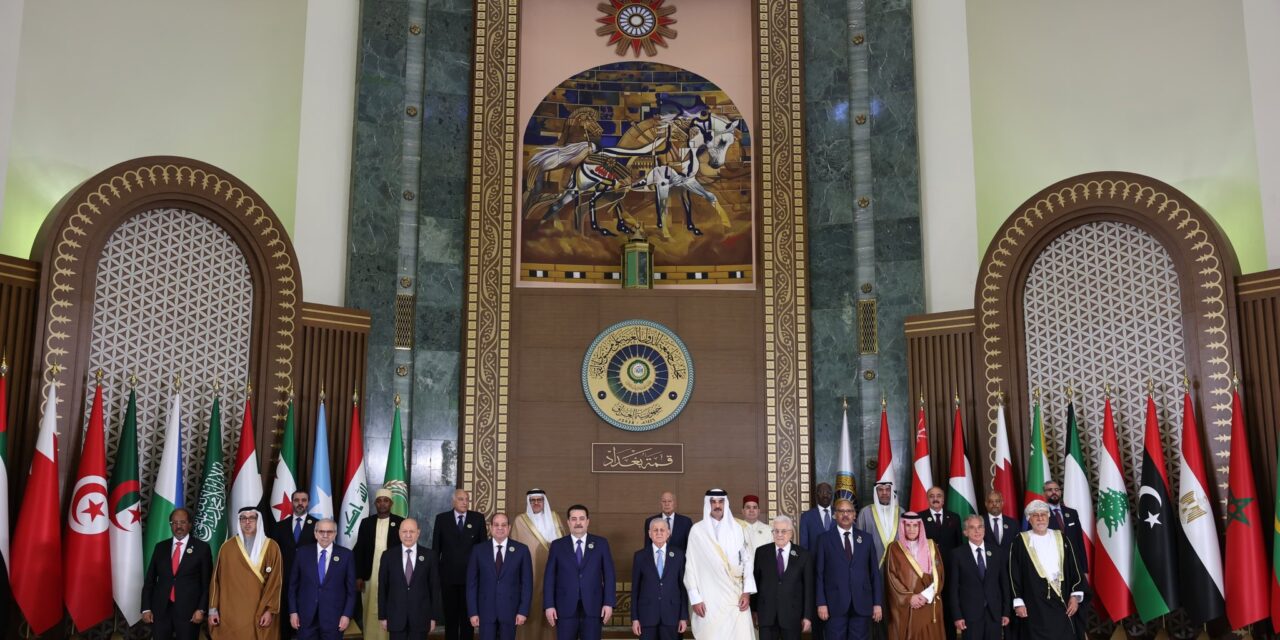

The 34th Arab League Summit in Baghdad, an annual meeting in the Arab region, could partially be interpreted as an unofficial election campaign for Prime Minister Mohammad Al-Sudani. Iraq’s sixth federal parliamentary elections are scheduled for November and a successful Arab League Summit showcases Sudani’s foreign policy credentials. Unfortunately for Sudani, the Iraqi press immediately deemed it a failure due to the low attendance from Arab leaders. From the public’s perspective, it also did not help that the Iraqi government emphasized the luxury and grandeur of the event. In a country rife with corruption, this type of government spending invites criticism.

The government spokesperson, Bassim Al-Awadi, and Sudani’s closest advisors were scrambling to defend the success of the summit, but the attendance spoke volumes. Notable absences include Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Emirati President Mohammed bin Zayed, Kuwaiti Emir Mishal Al-Sabah, Omani Sultan Haitham bin Tariq, and Jordanian King Abdullah II. The Arab League Summit is not like the United Nations General Assembly where each member state has a vote on important matters, it is more like the United Nations Security Council where certain members have a larger say than others, and while there is no veto power, the voices of states like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are louder than others.

The absence of these leaders was chalked up to their preoccupation with U.S. President Donald Trump’s regional tour only days prior to the main forum kicking off on May 17. Although Iraq has tried to position itself as a regional mediator in the last few years, leveraging its strong relationship with Iran and the United States, it has been notably absent in this latest round of dialogue. In the past, it played a role (alongside Oman) in talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

In addition to holding the summit too close to President Trump’s visit, the summit also shortly followed an emergency Arab League meeting in Cairo at the start of March. In many ways, that meeting stole the thunder of the Baghdad summit. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman and other regional leaders attended the emergency summit. It also marked the first attendance of Syrian President Ahmed Al-Shara, a point of much debate across Iraqi political talk shows ahead of the summit in Baghdad.

Iraq no longer needs to put on a show to signal to the world that it has returned to the playing field. Many other summits have been held, and larger sporting events like the 25th Arab Gulf Cup have done a better job at displaying security and stability. What Iraq needs today is substance and strategic planning. Summits and conferences with big slogans and little substance no longer serve a purpose and if anything, only exposes limitations and flaws of the Iraqi government and its political class.

This criticism is not limited to Iraq but extends to other actors in the region. When Dubai hosted Expo 2020 and Qatar hosted the 2022 FIFA World Cup, many wondered who the intended audience was, as both are small states with small populations. Likely in envy, Saudi then pursued the rights to host Expo 2030 and the 2034 FIFA World Cup. The Gulf model is one of an abundance of showy projects and events but with little substance or value to local populations. This is not an ideal model for Iraq to replicate.

There are many who have argued about the insignificance of the Arab League altogether, but from an Iraqi perspective, taking on the responsibility to host it also involves taking the opportunity to imbue it with new meaning. For example, this could have been an opportunity for Iraq to embrace the new Syria by building an agenda that draws on its own experience and focuses on the reintegration and reconstruction of its western neighbour. Iraq could have similarly leveraged its experience as a recipient of humanitarian and development aid to strategize a regional humanitarian and development program for other countries in crisis at a time of dwindling Western aid. Iraq did pledge $20 million in aid to Gaza and another $20 million to Lebanon, but these could have been framed as a starting fund for a broader initiative. Even if these conversations do not amount to immediate action, a summit of this stature is an opportunity to direct the conversation in the region in a uniquely Iraqi way, drawing on the country’s experience navigating regime change and post-conflict state building.

Hamzeh Hadad

Hamzeh Hadad is an adjunct fellow at the Center for a New American Security.