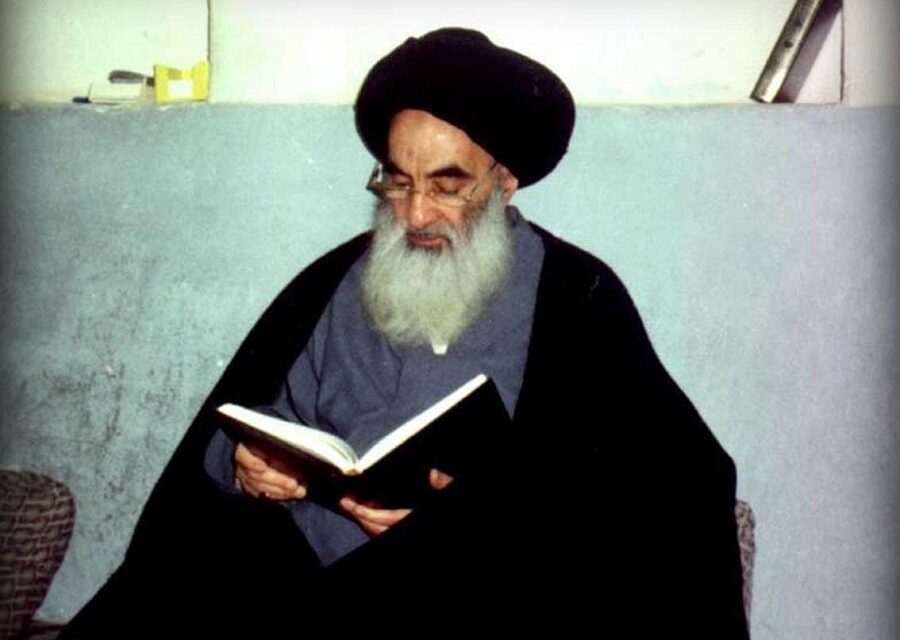

(Photo: Al-Khoei Foundation)

In a message last week conveyed through one of his representatives, Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani called on Iraqis to remain steadfast in their national principles and maintain hope for a better future. He emphasized that the country is moving toward recovery and stability, urging citizens not to give in to fear but to draw strength from their traditions.

Notably, he reminded Iraq’s Shia community that they possess “a great civilizational and intellectual heritage”—one that must be recognized, preserved, and actively cultivated. This reminder underscores a core theme in Sistani’s vision: that modern Iraq must root its political and moral future in a deeper historical awareness of its own values.

Many Iraqis are unaware of the intellectual tradition Sistani references, or that the strain of Shia political thought cultivated in Najaf over the past 120 years continues to shape his worldview today. This lineage bridges classical jurisprudence and modern constitutionalism and is best represented in the political theory of the late Ayatollah Muhammad Husayn Al-Na’ini (1860–1936).

This article explores the intellectual legacy connecting Na’ini and Sistani—two clerics from different eras who grappled with the challenge of governance through the imperative of confronting tyranny. Na’ini was a leading theorist of Iran’s 1905–1911 Constitutional Revolution, while Sistani has played a pivotal role in Iraq’s post-2003 transition. Despite the century separating them, their ideas share a commitment to constitutional limits, public representation, and a restrained but principled role for the religious scholar in political life.

Na’ini and the Iranian Constitutional Movement

At the start of the 20th century, Iran under the Qajar dynasty was beset by authoritarian rule, foreign interference, and economic decline. In response, reformers launched the Constitutional Revolution, demanding a legal order to limit royal absolutism. This led to the formation of a national assembly (majlis) and the drafting of a constitution in 1906. In 1909, the revolution found its most authoritative religious justification in the work of Na’ini.

In his treatise Tanbih al-Umma wa Tanzih al-Milla, Na’ini—one of the leading scholars of Najaf and a trusted associate of the grand marja of the time, Akhund Khorasani—offered a jurisprudential defense of constitutional government. He argued that while rule by the infallible Imam (the twelfth Imam in Shia Islam, believed to be in occultation) was ideal, constitutional rule was the best available alternative. The constitution, he asserted, was a tool to contain tyranny, distribute power, and promote justice. This, for Na’ini, did not contradict Islamic law but served its ethical aims.

The discourse of “combating despotism” (muharabat al-istibdad) had entered Islamic political thought around this time, popularized by figures like Jamal Al-Din Al-Afghani and Syrian writer Abdulrahman Al-Kawakibi. The latter’s 1905 work warned of the moral and political dangers of authoritarianism. Yet while the rejection of tyranny was clear, the nature of the system meant to replace it remained vague.

Na’ini filled this gap by articulating a vision of constitutional government that balanced Islamic legitimacy with modern institutional design. He wrote:

“The governing authority is representative of the nation and derives its legitimacy from it; the foundation for preserving the limits of authority is adherence to the provisions of the constitution. The constitution itself derives its legitimacy from not contradicting any clause of the rulings of the sacred sharia, and it includes all that is necessary to safeguard the interests of the country and the servants (of God).”

Furthermore, Na’ini’s conception of liberty (azadi) was more than just a check on tyranny – it was a moral virtue and a foundational civic ideal central to his political thought. In Tanbih al-Umma, he argued that constitutional government should not only restrain tyranny but also actively protect the “God-given freedoms” and equal rights of individuals and communities.

Discerning Sistani’s Political Thought

Sistani has never published a formal political treatise. His political thought must be pieced together from public statements, sermons, fatwas, and accounts from those close to his office. Despite this indirectness, his philosophy is coherent—blending moral authority with political restraint.

Although often labeled a quietist, this is a mischaracterization of Sistani’s approach. He avoids formal political office but intervenes decisively when moral or national stakes are high. A more accurate description might be a restrained interventionist—someone who acts to preserve national integrity rather than for partisan or political gain.

This became especially clear in 2003, when Sistani rejected the U.S.-led Coalition Provisional Authority’s plan to appoint a constitutional assembly. Instead, he insisted that Iraq’s constitution be drafted by a body elected by the Iraqi people. His intervention shifted U.S. policy and paved the way for Iraq’s first elections in January 2005. As Caroleen Marji Sayej observes, Sistani acted as a “guardian of democracy,” lending moral legitimacy to Iraq’s transition and prioritizing ethical leadership over direct political control.

Sistani has issued fatwas encouraging electoral participation, called for peaceful reform during protests, and mobilized citizens during the ISIS onslaught in 2014. He has consistently advocated for national unity, minority protection, combating corruption, and adherence to the constitution. For Sistani, Islam’s role is to provide the ethical framework for governance, rooted in popular legitimacy and the rule of law.

Despite differing contexts, Na’ini and Sistani share foundational principles. Both emphasized constitutional limits as safeguards against despotism and envisioned the Marja‘iyya not as a ruling institution but as a moral authority—a stabilizing force guiding society without directly governing it.

Their shared legacy affirms that the values forming the cornerstone of democratic governance, including liberty, constitutionalism, and popular sovereignty, are deeply embedded in the scholarly tradition of Najaf. As Iraq continues its pursuit of stability, Sistani’s recent call to recognize this intellectual heritage is not cultural nostalgia but a political call to action. The ideas cultivated in Najaf’s seminaries remain vital for imagining a just and inclusive Iraqi future.

Muhammad Fouad

Muhammad Fouad is a writer and researcher who specializes in Shia political affairs.