National strategic plans serve as crucial roadmaps for guiding the vision and implementation of a country’s policies and long-term developmental objectives. Addressing Iraq’s complex political and socio-economic challenges requires formulating and executing strategies that reflect the difficult operating environment including weak political will and institutionalized resistance to reform. However, the effectiveness of these strategies often falls short due to systemic issues in their lifecycle.

This paper seeks to dissect the inherent weaknesses in this process by introducing a unique assessment framework and applying it to two key national strategies. In doing so, we offer a set of best practices that can serve to guide Iraqi practitioners and international partners on how to improve strategic planning processes.

Assessing the National Strategies Life Cycle

The life cycle of a national strategy comprises four key stages: formulation, adoption, implementation, and evaluation. Each stage presents its own set of challenges and involves varying roles for stakeholders. These stages are interdependent; for instance, the successful drafting of a national strategy partly hinges on the mechanism for its eventual adoption. Likewise, the effective implementation of a national strategy depends in part on the quality of the evaluation process. In essence, the process is dynamic and cyclical rather than linear and finite.

By analyzing a variety of national strategies in Iraq, we identify weaknesses in the national strategies life cycle. Typically, these documents fail to prioritize strategic goals, opting instead to offer an overly ambitious laundry list of objectives that cannot be easily measured or translated into programmatic activities. Furthermore, data is often too outdated to offer any utility in establishing baselines. Additionally, poorly defined budget allocations for implementing these national strategies create avoidable obstacles.

On the implementation front, national strategies typically involve a multi-agency approach, but competition and contestation between ministries and departments that are influenced by a broad spectrum of political actors make coordination over the implementation process an arduous task.

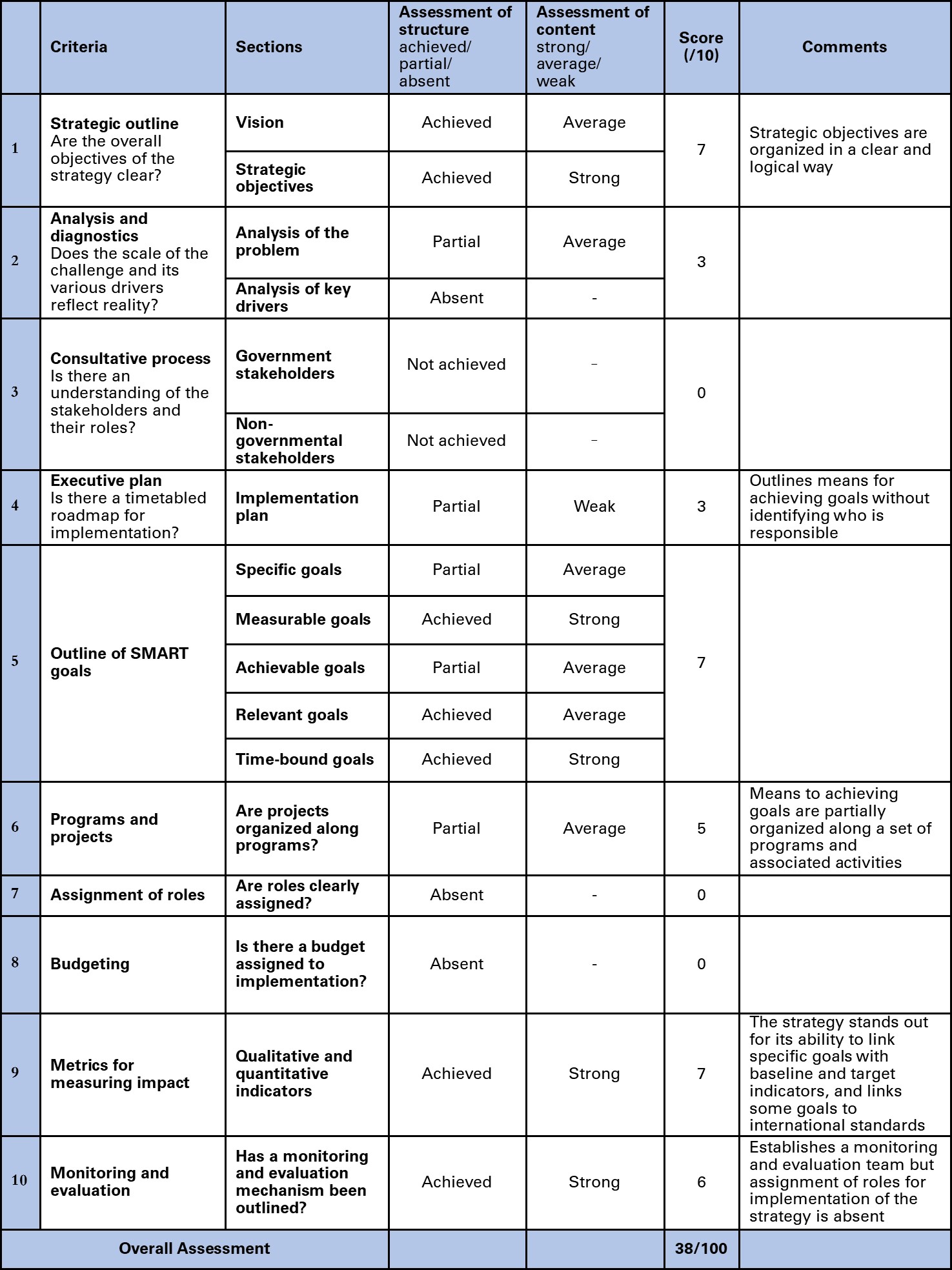

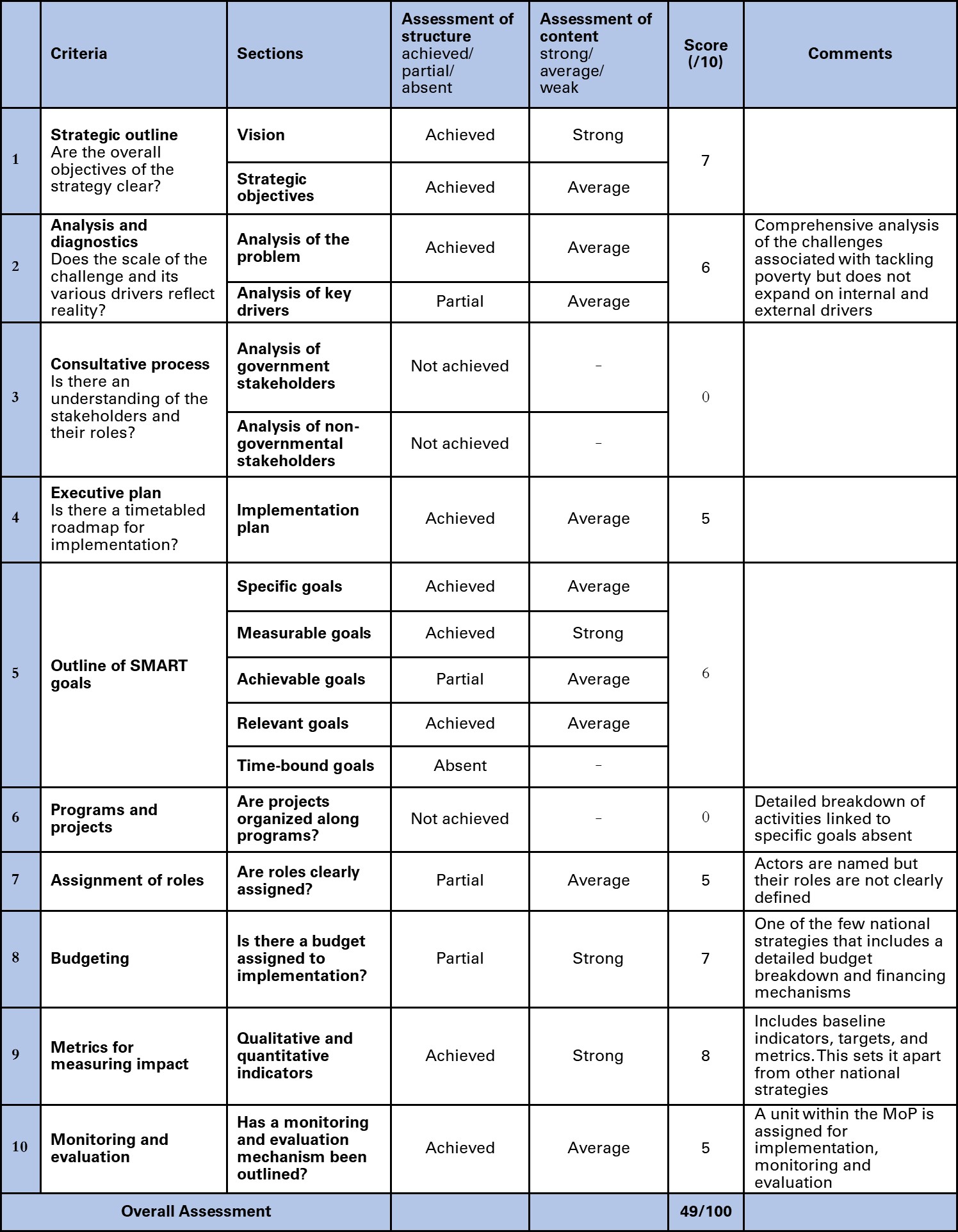

Our assessment of national strategies is based on a framework that we have developed, featuring ten criteria. These range from the ability to convey strategic objectives with clarity, whether the diagnosis of problems is comprehensive and reflects a good understanding of reality, the existence of an implementation plan that includes a clear assignment of roles and a budget breakdown, the extent to which the objectives are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), and whether there is a mechanism for monitoring and evaluating progress.

Each criterion is assigned a score out of 10 based on the extent to which the national strategy has incorporated the criterion, giving an overall score out of 100. For the purposes of this paper, we examine two national strategies in Iraq and illustrate their strengths and weaknesses. We explore the Iraq Vision for Sustainable Development 2030, and the Poverty Reduction Strategy 2018-2022.

Iraq Vision 2030 was formulated during the Haider Al-Abadi administration with support from the World Bank. As its name suggests, it aims to delineate a roadmap for sustainable development by the year 2030. According to our assessment framework, the document’s primary weakness lies in the absence of stakeholder mapping and clear assignment of roles.

What sets Iraq Vision apart is its utilization of metrics to establish objectives and targets, along with the integration of international indicators into its SMART objectives. Moreover, it establishes a monitoring and evaluation team. However, Iraq Vision 2030 falls short in two areas: it lacks a budget plan and fails to provide projections for the funding necessary to achieve its objectives.

Table 1: Assessment of the Iraq Vision for Sustainable Development 2030

Compared to other national plans, the five-year Poverty Reduction Strategy is exceptional in some respects. Each program within the strategy identifies an associated budget and proposes individual financing mechanisms. The strategy was produced in collaboration with the World Bank and included a technical drafting committee consisting of more than 20 members from across government institutions. The Ministry of Planning was the primary lead, and the strategy includes the establishment of a poverty reduction unit within the ministry. But one of the primary weaknesses of the plan is that it fails to establish a baseline measurement of the poverty rate in Iraq, which poses challenges in measuring progress.

Table 2: Assessment of the Poverty Reduction Strategy 2018-2022

Key Features of the National Strategies Life Cycle

Drawing on a variety of Iraqi national strategies, and an analysis of the operating environment, several common features related to the national strategies life cycle can be observed and form the basis for developing a set of best practices:

- Many national strategies fail to prioritize strategic goals, opting instead for a long list of generic objectives that cannot be easily measured or translated into programmatic activities. These strategies are both highly ambitious and lacking the tools and capacities to achieve their stated objectives. They articulate a vision of institutional overhaul, rather than focusing on limited areas of improvement and creating islands of good practice.

- The utilization of data within national strategies is a primary weakness. Many strategies fail to identify and draw on baseline data, a crucial aspect of strategic planning because it enables implementors to measure progress. In the absence of baseline data, the way in which success or failure is defined becomes highly subjective.

- Where data is utilized, its unreliability poses a major challenge. There are many instances where data is far too outdated to offer any utility in establishing baselines. Conflicting figures from multiple agencies also exist, for example, on unemployment and poverty rates. This leads to unrealistic targets being set. For example, electricity output targets in the National Development Plan consistently fail to be achieved because the complex dynamics related to electricity generation are not factored into the targets. Data across national strategies can be inconsistent and contradictory. For example, oil production targets in the National Development Plan differ from those in the Integrated National Energy Strategy.

- The drafting process often lacks a good degree of inclusivity. Even where cross-ministerial committees are formed to draft national strategies, they tend to neglect a comprehensive consultation process that incorporates the voices of actors outside of the government sector. This poses a real problem at the implementation stage, particularly when a broader group of stakeholders is needed to assist with programming. For instance, the national water strategy is produced by the Ministry of Water Resources, with the inclusion of the Ministry of Agriculture. During the implementation phase, local governments, who were left out of the process, become critical to the success of the strategy, but their lack of inclusion leads to an uncooperative working environment.

- Where there is a misalignment between the timescale of a national strategy and the length of a government’s term, this can create an ownership deficit. For instance, the much-heralded White Paper on Financial Reforms was approved by the Mustafa Al-Kadhimi government towards the end of 2020. Much of its strategic targets operate on a five-year timescale. But the short-lived nature of that government meant that little progress was made in delivering on its strategy’s commitments. The incoming Mohammed Al-Sudani government subsequently had little reason to embrace the White Paper or the institutional arrangements associated with its implementation, opting instead to formulate its own priorities on financial reforms.

- Misalignment between national strategies and the Government Program leads to a confused policymaking climate. Incoming governments fail to integrate existing national strategies into the Government Program or amend national strategies to align with their own targets. Ultimately, a process of realignment needs to occur, whereby national strategies are revised to reflect the incoming government’s policy agenda.

- Implementation plans for national strategies are often weak when it comes to defining the roles of stakeholders. This can be seen with the case studies outlined above. There is a lack of specificity about what each stakeholder is expected to deliver, and little emphasis is placed on devising mechanisms to ensure cooperation between them. Furthermore, where national strategies identify a set of priority areas to focus on, these are typically not reflected in the implementation plan, such as the timeline of activities or the share of funding going to priority areas.

- Budget allocations for the implementation of national strategies are one of the biggest obstacles. The federal budget rarely earmarks funds for specific national strategies unless those responsible for implementation exert considerable effort to lobby for it, as is the case with the Poverty Reduction Strategy. In most instances, government departments that are involved in implementation are required to secure budgets for activities and projects on an individual basis. This poses major financial and administrative obstacles to securing funds and ensuring sustainability of funding.

- The monitoring and evaluation phase of the life cycle is typically absent or weak. In instances where there is an attempt to assess progress, there is almost always a failure to distinguish between outputs and outcomes. Success tends to be defined by the number of activities completed rather than their impact in achieving the stated strategic goals. Impact therefore becomes a secondary consideration, and projects that have poor outcomes may continue to be repeated within the implementation cycle.

- Related to the evaluative process, accountability, and oversight on implementation of national strategies are notoriously weak. While the Ministry of Planning is responsible for monitoring development projects, its tools and processes for assessing impact are inadequate. In instances where there is interim progress reporting, these reports do not convey sufficient insights into the quality of activities, focusing instead on quantity of outputs. Furthermore, there are few repercussions for stakeholders who fail to meet their targets in accordance with implementation plans.

The end result of these structural and procedural weaknesses on the national strategies life cycle is a void between what national strategies set out to achieve and what actually materializes in reality. By the end of a strategy’s term, targets have largely not been achieved, and there are few evaluative insights into what went wrong. Policymakers will then reflexively restart the cycle and begin drafting a new strategy, only to make the same mistakes.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of national strategies in Iraq is hindered by multiple interlinked procedural and structural weaknesses. To improve the success rates of these strategies, it is imperative to focus on enhancing the quality of data, ensuring inclusive stakeholder engagement, aligning strategies more closely with government agendas, and developing robust evaluation frameworks. Reforming these aspects can lead to a more coherent and effective strategic planning process that better addresses Iraq’s development and governance needs.

Ali Al-Mawlawi

Ali Al-Mawlawi is an analyst who specialises in Iraq’s political economy and governance reform.

Ghazwan Al-Manhalawi

Ghazwan Al-Manhalawi is director of Platform for Sustainable Development (PSDIraq) and specialises in data analysis and public sector reform.