This new parliamentary bloc, depending on its performance in conjunction with Kadhimi’s, could serve as the incumbent’s electoral list. However, it remains unclear whether Kadhimi himself plans to be a candidate in elections or allow this bloc to run independent of his name leading the list. The latter would allow him to keep his word prior to becoming prime minister-designate, and may prove to be the most successful route for a full term in office.

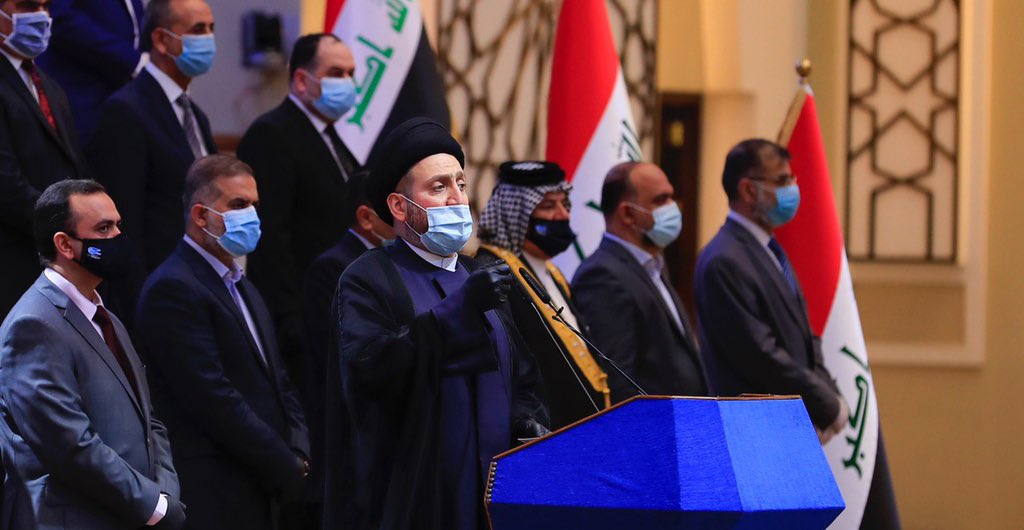

The formation of the parliamentary bloc Iraqiyoon were led by former Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi, head of the Nasr bloc. But once the hard work was done, Abadi was reluctant to go through with its announcement, paving the way for Kadhimi to have Hakim announce it instead, and take all the credit. This has momentarily strained the relationship between Kadhimi and his former boss who nominated him as head of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service in 2016. But the possibility of the two joining forces as we near elections remains a possibility. They do, after all, share a similar vision and ideology.

The challenge facing all Iraq’s political leaders is the fragmentation of the Iraqi political scene. Currently, most political leaders have between 18 and 25 members of parliament within their bloc. This extends to the Fateh coalition (when broken down by party). The major exception is the Sadrist Movement which has around 50 members within Sairoon, but even that is considerably lower than previous election winners. For example, in 2010, the Iraqiya coalition won 91 seats and in 2014, the State of Law coalition won 92 seats. This kind of mass voter mobilization will be difficult for a new political movement to inspire in the next elections. The reason these two coalitions had such success in the past was because former prime ministers Ayad Allawi and Nouri Al-Maliki were able to reap the benefits of the patronage networks that were sown under their premierships. Additionally, there was less public skepticism around politics and a higher voter turnout rate. In addition, public opinion data from Iraq shows that in 2011 and 2014, 69% and 74% of surveyed Iraqis expressed some degree of trust in the cabinet. By 2018, this number shot down to 35%. It will be difficult to replicate the results of these elections with an election campaign based heavily on rhetoric, and less on clientelism, as we saw with Abadi’s underachieving performance in 2018.

Abadi could have capitalized more on his military successes in office during the 2018 election, but he chose to limit populist rhetoric during his campaigning. Instead of highlighting bringing Kirkuk under federal authority, he chose to focus on his vision for all Iraqis. While his electoral list’s name was chosen to commemorate the victory against Da’ish, outside of this, he did not push a message of one group of Iraqis defeating another. In addition, previous experiences have demonstrated that personal popularity and media hype around a political party rarely result in votes. Rather, what we see is oftentimes the opposite. Take for example, the Civil Democratic Movement in 2014, which enjoyed a lot of popularity, particularly on social media, and received support from major Iraqi voices like journalist Dr. Nabil Jassim. Ultimately, it was only able to win three seats. Similarly, in 2018, the revival of the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) through protest participation and through its cooperation with the Sadrist Movement won the list the most seats in 2018, but only two of the 54 seats went to members of the ICP. Another example is current advisor to the prime minister on women’s affairs, Dr. Hanan Al-Fatlawi. Her popularity in her home province of Babil failed to win her a seat in 2018 and her party’s list only won three seats.

This serves as a lesson not only for the political blocs being formed by the establishment, but also for the new movements forming from the aftermath of nationwide protests across Baghdad and the south from October 2019 and onwards. These new political movements are doubtlessly a positive development as they will provide an alternative to the status quo. However, they will face similar difficulties in achieving electoral success. While hundreds of thousands of young Iraqis came out to protest, millions of Iraqis more (despite lower turnout in 2018) go out to vote, oftentimes with their mind made up prior to any campaigning. Therefore, the target needs to be convincing non-partisan Iraqis that are skeptical of change to not be complacent come election day.

There have been documented violations at previous Iraqi elections, including, most recently, in the 2018 federal election. However, these violations have not been widespread enough to the extent that results are predictable, which is why all political parties spend massively on election campaigns. The other factor to keep in mind is the high turnover of elected representatives seen in each election cycle. In fact, many who won seats in the 2018 election and are accused of election violations are fearful of early elections due to their current unpopularity and inability to prevent future violations from taking place by an Independent High Electoral Commission that has integrity. Therefore, election results and voter sentiment cannot be discredited in analysis.

The next election will be a massive test for all of Iraq, from the voters that chose to boycott in 2018, to the established political parties dealing with dwindling popularity, to the new political movements that will join in hopes of providing an alternative. Whatever the results will be, free and fair elections by 2022 are a must for Iraq. There is no other alternative to govern a diverse nation that has seen too much oppression from authoritarian regimes.