(Hospital Midwife holds newborn baby in west Mosul. Photo: UNFPA)

The fraught federal relationship between the Iraqi government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government remains a dominant feature of broader Iraqi politics. The issue is not only the default confessionalism in Iraq’s top leadership posts with many Kurds assuming the presidency is reserved for them, but also revenue sharing between Baghdad and Erbil. Article 121, section three, of the 2005 Iraqi Constitution states that “Regions and governorates shall be allocated an equitable share of the national revenues sufficient to discharge their responsibilities and duties, but having regard to their resources, needs, and the percentage of their population.”

The problem, of course, is determining what percentage of the population each governorate represents. The last real and generally scientific census in Iraq was in 1957. At the time, Iraq had a population of 6.3 million. That’s just two-thirds of Baghdad’s population today.

What was the Basis of the 13 Percent KRG Allocation?

Among Iraq’s various ethnic and sectarian groups, their relative proportion of the population remains contentious. Former President Saddam Hussein was in theory a Baathist but in reality was a Sunni Arab chauvinist. He stripped many Iraqi Shi’ites—both Arabs and Kurds—of their citizenship, deporting many thousand to Iran, and sought to ethnically cleanse regions like Kirkuk where disfavored groups lived astride significant oil and agricultural resources.

The international community met Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait with broad sanctions. Rather than remedy his behavior, Saddam sought to utilize the world’s media for his own propaganda purposes. While he built palaces in Baghdad for his family and close associates, and while baby formula was exported for profit, Saddam’s regime denied adequate food and medicine to some Shi’ite communities to compel the lifting of sanctions. The UN Security Council responded on April 14, 1995, with Resolution 986, which launched the “Oil-for-Food” program. While the program itself was complicated—and riddled with corruption both in Baghdad and Turtle Bay—its rations were predicated on the assumption that the Kurdistan Regional Government-controlled portions of the country held 13 percent of Iraq’s population.

In lieu of a census, post-2003 Iraqi governments have maintained that figure. While former oil minister and current Prime Minister Adil Abd Al-Mahdi—who has long had a close political relationship and friendship with Masoud Barzani, the Kurdistan region’s former president and paramount power—raised Iraqi Kurdistan’s proportion of Iraq’s oil revenue to 17 percent.

Whether that figure is 13 or 17 percent, many disputes continue: Does the percentage apply to gross or net proceeds? Does it apply only to the central government’s revenue, or should Kurdish oil go into the central kitty? Should funding received from the International Monetary Fund or World Bank also be subject to division based on the percentage?

Those disputes have continued with various degrees of animosity and unilateralism for 15 years with Kurds unilaterally exporting oil and authorities in Baghdad often cutting financial transfer to Erbil as a result. And while many diplomats, Iraqi politicians, and financial analysts gauge their analysis to the resolution of disputes between Baghdad and Erbil based on a revenue sharing percentage between 13 and 17 percent, changing demography may soon upend current assumptions.

The Kurdistan Regional Government’s Ministry of Planning maintains a statistical agency, the Kurdistan Regional Statistics Office, charged with statistical gathering and conducting a basic census. Its reports, however, show no methodology and are often are years delayed. The Iraqi government, meanwhile, is currently planning a new comprehensive census, tentatively set for October 2020.

There are many reasons for the Iraqi government to seek a new census. Iraq has undergone a significant baby boom. Forty percent of Iraqis were born after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and so will enter the labor force in just a few years. Sixty percent of Iraqis were born after the 1991 liberation of Kuwait. By 2030, Iraq could very well have over 50 million people, twice its population at the time of the U.S. invasion.

Could Kurds Fall Below 13 Percent of Iraq’s Population?

Despite continued infrastructure problems and government services, Iraqis are also becoming wealthier. Iraqi per capita income has more than quadrupled since 2003, and shows signs of increasing even further. Iraq’s per capita income is now higher than Algeria, South Africa, and Costa Rica, and is approaching that of Azerbaijan. Iraqi Kurdistan, of course, has enjoyed greater security and investment than the remainder of Iraq in the post-2003 period and so its affluence is even greater. Baghdadis celebrate blast walls coming down in the past several months, but in Sulaymaniyah and Erbil, they never went up.

With affluence, of course, fertility—the number of children each woman has—declines. Iraqi Kurdistan’s growth rate—by its own statistics—is now 2.3 percent, although this figure appears largely derived by copying from World Bank data that included areas outside of Iraqi Kurdistan. In the rest of Iraq, growth rates might also level off but for now estimates are higher and range between 2.5 and 2.8 percent. As birthrates in southern and central Iraq continue to far outpace those in Iraqi Kurdistan, the relative proportion between Arab and Kurds in Iraq will continue to grow. While Iraqi Kurds have grown accustomed to demanding between 13 and 17 percent of Iraq’s revenue, within a decade, Iraqi Kurds might represent only 10-12 percent of Iraq’s population.

The ramifications of this on Iraqi politics and society could be serious. Many Kurds might demand continued utilization of inflated population statistics, and there will always be a temptation for some politicians, as Abd Al-Mahdi did before, simply to bribe Barzani with an inflated figure. But, with poor infrastructure and protests in southern Iraq already ending one prime minister’s hopes of a continued mandate and quite possibly threatening Abd Al-Mahdi’s tenure, the notion among ordinary Iraqis and politicians in Baghdad that Kurds should essentially be counted as more than any other individual becomes tenuous. In Lebanon, after all, it was the inability of the system to account for changing demography which contributed to if not caused the civil war.

This is not to suggest that Iraq is headed to civil war; quite the contrary: Iraq is quite resilient and, despite the messy ‘kebob-making’ of the Iraqi political process, it generally works, at least when compared to its neighbors. But some difficult choices loom. Rather than prepare for the 50 million mark with sustainable reform, Abd Al-Mahdi’s team appears more inclined to focus on the short-term without regard to long-term sustainability.

What Will a Lower Population Proportion mean for Iraqi Kurds?

In Iraqi Kurdistan, however, the problems may be compounded. While the relative proportion between Kurd and Arab may shift, both populations will grow. The Kurdistan Regional Government’s administrative bloat continues to drain its economy. The recent shooting of a Turkish intelligence officer under diplomatic cover in Erbil and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s furious reaction also highlights the Iraqi Kurdish economy’s dependence upon Turkey’s goodwill. Despite their shiny exteriors, the vacancy rate of apartments and houses in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah are high—perhaps, according to local estimates, 70 percent. Corruption, meanwhile, dampens foreign investor enthusiasm. The Kurdistan Regional Government will therefore not only continue to face the current strains on its economy that it has hitherto been unable to address effectively, but will also simultaneously face the possibility of reduction of its share of Iraqi revenue below the level to which it has become accustomed.

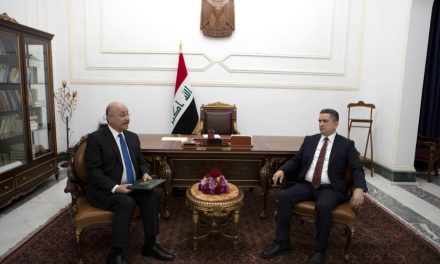

Iraqis may also begin to question whether the current Kurdish representation in Baghdad is appropriate. The late Jalal Talabani and Fuad Masum largely took Iraq’s presidency simply because they were Kurds; indeed, Masum had no other basis to seek the post. Barham Salih to some extent was also nominated because he was Kurdish although he had to campaign actively among Sunni and Shi’ite Arabs and other political groups in order to win the post and, to serve a second term, he will likely need to rely more on Arabs than Kurds. Transcending ethnicity is, of course, healthy for Iraq and Barham is a skilled politician who is enthusiastic to do so. Other Kurds, however, are less skilled and have fewer cross-ethnic, cross-sectarian ties. It is conceivable that as Iraq passes the 50-million-person mark, majority Shi’ite Arabs will demand two of the top three posts, especially as the growing diversity of political trends and lists means that Shi’ites and other Iraqi groupings do not speak with one voice. The question then becomes whether the Kurds will willingly agree to a reduction in posts commensurate with a reduction in their proportion of the population or seek to filibuster government formation in order to maintain their current influence.

French sociologist Auguste Comte (1798 -1857) reportedly coined the phrase, “Demographics is destiny.” And, indeed it is. But while Iraqi politicians continue to operate on a template shaped by the 1957 census and fine-tuned by Oil-for-Food ration cards, the assumptions and proportions inherited from these processes may no longer be tenable. Recovery, security, and affluence may be good news stories, but they also herald demographic change which Iraqi and Iraqi Kurdish leaders have yet to address, let alone apparently consider.

Michael Rubin

Michael Rubin is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a senior lecturer at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. He was editor of Middle East Quarterly and is author of Kurdistan Rising? (AEI, 2016). His most recent book chapter is on the history of KRG corruption in Routledge Handbook of the Kurds (Routledge, 2018). He received his Ph.D. in history at Yale University, and previously taught at both the Universities of Sulaymani and Salahuddin in Iraqi Kurdistan.