Academics and experts are divided with regards to compulsory military service in Iraq. After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq, Paul Bremer issued a decree to dissolve the Iraqi Army, which consisted of 365,000 soldiers. This decision was seen by some as a loss, given that Iraq had one of the strongest armies in the region and arguably in the world. However, others saw it as an abolition of slavery to the military institution imposed by the former regime with compulsory military service that created a large army with weak morale.

Historically, compulsory military service in Iraq was introduced by the Ottomans during the reign of Omar Pasha. While the communities in Baghdad welcomed the decision, Iraqi tribes starting from Diyala down the Middle Euphrates refused it. Civil disobedience spread and led to attacks, resulting in bloody encounters between the Iraqi tribes and Ottomans forces in which hundreds were killed. Nevertheless, the compulsory military services were ratified as a fixed law during the reign of Midhat Pasha.

The mandatory services continued in Iraq until WWI and the fall of Iraq under the administration of the British. During the establishment of the monarchy in Iraq in 1921, there were several attempts by King Faisal I to establish mandatory service, while the Iraqi tribes continuously refused to involve their sons in the military out of fear that the institution would be politically abused.

Indeed, one year after applying mandatory military service in 1935, there was a military coup under the leadership of Bakr Sidqi, which was the first attempt by the military to overstep its legal and constitutional boundaries, later leading to political assassinations. It is worth mentioning that the political ambitions of the military never stopped there and then, instead always looking for a more active role in government, and often leading to many military coupes in Iraq.

The consistent involvement of the military in Iraqi politics paved the path for a coup by a political party with a distinctive ideology, the Ba’ath Party. The result was the politicization of the military as opposed to the militarization of politics that was happening in the past and the establishment of an “ideological army”. This was a dangerous precedence contradicting the principles of establishing national armies in the Middle East. Nonetheless, since the introduction of compulsory military service until the fall of the Ba’ath regime in 2003, the militarization of society led to the rise of several strong military leaders encouraged by the number of military personnel available to engage in coups and wars.

This begs the questions of whether the mandatory military service helped Iraqi society and to what extent? Could it ever serve Iraqi society?

The Changing Role of the Military in Society

Establishing mandatory military service today will be repeating the mistakes committed prior to 2003, given that it will potentially increase the members of the armed forces to 10 million. This will likely shift the loyalty of the youth to the military institutions as opposed to the democratic system, increasing the dangers of military coups. The Iraqi constitution contains many safety nets that protect the country from falling back to dictatorship and liberate society from the traditional view about the role of the military in protecting the people through non-interference in politics, a role that has proved its failure in Iraqi history.

Many view compulsory military service as an approach to social reform, often seeing it as the only way to strengthen ties of the youth with their homeland. The fact that a democratizing society suffers from certain social ills does not warrant passing laws that might not be in line with democratic standards, especially as these values have been gradually growing for the past 16 years. The respect of citizens and their love for their country cannot come through coercion. Also, correcting social problems does not happen at the age of 18 as it should start earlier.

It won’t be possible to fix the negative relation between the Iraqi state and its citizens from previous regimes through just compulsory military service. On top of that, the drawback of mandatory military service is the possibility of jeopardizing the professionalism of military institutions through behavior and cultures that are ill-suited if they are filled with service members against their will.

Increased national belonging can happen through civil service that can include unemployed youth. With sectors in need of support and youth in need of employment, this can be beneficial to both employers and Iraqi youth.

An Opportunity for Corruption

Compulsory military service might provide another opportunity for corruption to grow. The draft of the military service law, as required by the constitution, contains clauses that allow for exemptions, with special authority given to the minister of defence to provide these. Given the deteriorated situation of Iraqi administrative procedures, there are no realistic measures on the ground that can ensure complete transparency. Furthermore, there is the possibility to compensate for military service with a sum of money, which would privilege the upper class with the ability to avoid military service and put a heavy burden on the less affluent families with daily wage workers, creating a wedge between the different social classes.

Contradicting the Spirit of the Constitution

By examining the proposed law for compulsory military service, we find several discrepancies and violations of the spirit of the Constitution. For instance, Article 23 of the draft law gives preferences for those who have conducted the mandatory service over those who have not, which violates Article 22 of the Constitution calling for equal opportunity for all Iraqis.

Article 24 of the draft military service law gives the state the right to fire state employees from their work if they do not conduct their mandatory military service for whatever reason, which is in violation of Article 22 of the constitution that guarantees the right of work for all Iraqis.

Article 25 of the draft law allows for the prevention of travel for those that have not conducted their military service, contradicting Article 44 of the Iraqi Constitution which gives the Iraqi citizen the freedom to travel and live inside and outside the country.

The same applies to Article 27 of the draft law which prevents citizens from joining unions and societies during the period of their military service, which violates Article 39 of the constitution, which states that joining unions and societies is a personal right and the state does not have the right to prevent anyone from joining.

These violations of the spirit of the constitution provide a fertile ground for authoritarianism to grow again, especially when it comes to loyalty to the military institutions instead of the state and controlling citizens under the pretext of military discipline.

Sectarianism, Minorities, and Women in the Military

Advocates of compulsory military service speak of its role in building an army that transcends sectarianism and is able to prevent emergencies like the ones that warranted issuing the ‘Jihad Fatwa’ by the religious authority in Najaf after Da’ish invaded Mosul. While this reasoning seems to be acceptable, it does not warrant drafting society for compulsory military service. The Iraqi Security Forces historically have been majority Shia, a reflection of Iraq’s demographics and the events leading to the fall of Mosul was not because of Iraqi Security Forces’ numbers lacking, rather a failure at the leadership level of certain divisions.

There is also controversy around women in the Iraqi military. The Kingdom of Morocco reinstated mandatory military service 11 years after abolishing it, with a unique move to include women based on the principles of equal rights. If compulsory military service was to be reinstated in Iraq, would excluding women not mean excluding them from the opportunity to grow their national belonging, equal to that of men? Furthermore, unemployment is about 12% amongst women compared to 7.3% amongst men. If military service was an approach to combat unemployment, would that not require the inclusion of women in the military service? On the other hand, including women would contradict sharply with the norms and traditions of Iraq’s society that resists women being engaged in any military activities.

That said, military service would also cause an imbalance in civil institutions. Men would be less represented given that they are busy with military service.

Ethnic balance is also an issue that mandatory military service is supposed to tackle. Before 2003, when military service was mandatory for each Iraqi, the Kurds and the minorities would serve in ‘light’ military formations, called the ‘Fursan’ (Knights) led by tribal leaders that fought against internal threats like saboteurs and not enemies from behind the borders. As for the Peshmerga, officially recognized by the Iraqi constitution as a local force, it plays the role of an army specific to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and is practically independent from Baghdad, despite the latter paying its salaries and being theoretically under the command of the Iraqi Commander in Chief. The question arises: if compulsory military service was to be reinstated, where would a Kurdish citizen serve, in the Iraqi army or the Peshmerga?

The Economic Implications of Compulsory Military Service

There are also economic implications in passing this law. The job market requires a competent workforce and not more soldiers. One of the major questions posed by experts and researchers is that the supply of workforce is represented mainly by university graduates. In other words, there is a large number of university graduates who have skills of limited use in the private sector. By reinstating the compulsory military service, many will choose to continue their university education in order to avoid military service or reduce the amount of time they need to serve. This will put a lot of pressure on educational institutions who have limited capacity and inflate the number of graduates more than the actual job market requires, leading to even more incompetent job seekers. How will the state deal with these issues? And what are the measures to make sure that graduates who finished military service will actually be able to find a job, given that leaving young people with military training without a job can pose a risk of them joining illegal violent activities.

Career Armies Are More Effective

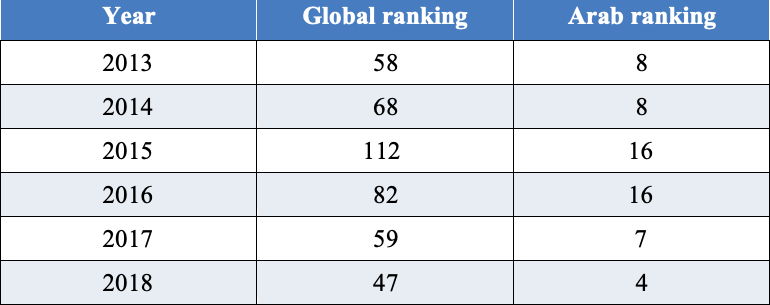

Those who chose the military as a career instead of being mandatorily drafted will be more competent. The new Iraqi army established after 2003 showed the capacity to develop fast. The presence of an enemy like Da’ish motivated security and defence officials to improve the combat and leadership capacities of the Iraqi army. Based on the Global Firepower Index, the Iraqi army achieved important progress in the last few years.

Progress by 65 spots has been achieved with Iraq having a career army.

Furthermore, the Peshmerga and the Popular Mobilization Forces proved to be effective in fighting against Da’ish and were also voluntary forces. Therefore, it is fair to say that career soldiers can be more effective. The military institution can choose between them based on competency, something that mandatory drafting will hinder. The Iraqi Army is in need of training and equipment and not necessarily more numbers. Furthermore, without addressing the other issues related to this move, if the Popular Mobilization Forces were integrated into the Iraqi Army, it would increase the number of competent and battle-hardened fighters in Iraq. Nonetheless, the solution lies in competence and not numbers.

One of the most important lessons learned during the war against Da’ish is that the collapse of five Iraqi Army divisions was due to lack of training, intelligence support, logistical issues, corruption, and lack of professionalism amongst some of the military leaders, as stated by the Iraqi Parliament’s report on the fall of Mosul. The same parliament will be voting on the mandatory military service law, knowing that most of these issues are still in place. The question remains whether they have thought about how this law will impact the future of the armed forces and the challenges it faces.

Lina Musawi

Lina Musawi is a political researcher and journalist. She is completing a Master’s degree in conflict resolution and peace building at University of Baghdad.