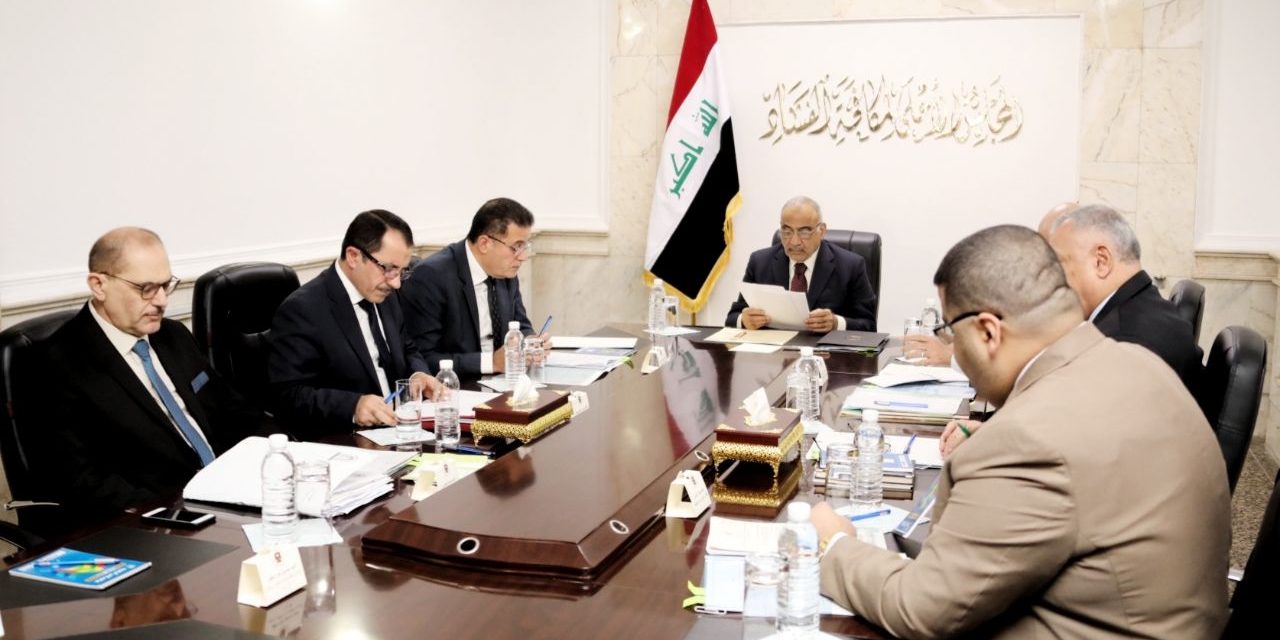

(Prime Minister Adil Abd Al-Mahdi chairs meeting of the High Council for Combatting Corruption)

Iraqi Prime Minister Adil Abd Al-Mahdi established ‘The High Council for Combatting Corruption’ to tackle rampant corruption under executive order number 70. The establishment of the council comes just as Transparency International published its recent annual report, classifying Iraq as the sixth most corrupt country in the Arab region and amongst the top 12 most corrupt countries in the world.

Chaired by the Prime Minister himself, the council is made up of the following members: the Head of the Federal Board of Supreme Audit, two judges from the Supreme Judicial Council, the Head of Integrity Commission, a representative of the Inspector Generals’ Offices, and the Legal Department Director General at the Prime Minister’s Office.

The Prime Minister expressed “a lot of hope in the council,” promising to craft a grand strategy to tackle corruption in the country. Without a doubt, establishing this council signals that the government is prioritizing anti-corruption, just like its counterpart, the High Council of National Security established by former Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi, which was instrumental in coordinating the security effort in the fight against Da’ish.

Iraqi politics is full of controversies and reservations, but the outrage of some parliamentarians expressed over establishing the council was important to note. The claims against the council can be summarized in three different categories.

In the first category, the opposition against the council is political. Those opposing the establishment of the council say that such entities are not effective and the only justification for them is to pretend that the government is doing something against corruption. As long as there is no political will, which does not seem to be present in the current government, corruption will not be tackled. Some go further and claim that it is not possible to eradicate corruption in Iraq without “changing the entire political elite in the country”. Otherwise, any effort in this regard is cosmetic in nature.

The second group of opposition uses legal arguments. They claim that establishing such a council is against the separation of powers in the country as prescribed by the constitution, because it gathers executive, auditory, and judicial bodies in one apparatus. On the other hand, it diminishes the supervisory and legislative role of the parliament in combating corruption. Others criticized this step and regarded it as ‘illegal’ because this council does not have a law that governs it.

The third type of criticism is about the practicality of the council. Many opponents claim that the executive branch is entangled with corruption at one hand and has enough apparatuses that are supposed to tackle corruption on the other hand. The question then becomes, why not start immediately with the means available without the additional layer of bureaucracy?

Some of these arguments are on point, and should be taken seriously. However, a lot of what has been said about the council is political. Both parliamentarians, past and present, are trying to score political points against the government by taking cheap shots on popular TV shows, without attempting to genuinely assess the council and its purposes.

It is important to judge what is valid criticism and what is not. The claim that the council is unconstitutional because it combines different branches of government is wrong. One of the failures in tackling corruption in the past is due to the lack of coordination between state institutions. The council is an umbrella committee, rather than a stand-alone organization, that aims to gather the different branches and apparatuses at one table to coordinate mutual efforts against corruption. Therefore, it does not require a law to operate, and its existence is not a violation of the constitution. Sadly, this has been claimed by parliamentarians who are members of Parliament’s anti-corruption committee, which shows their lack of legal knowledge.

Communication in general needs to increase and be shared, let alone between state entities that tackle corruption. This council could facilitate this, which would mean less time is needed to investigate, process, and execute corruption cases. For instance, in the past we have often heard from the Integrity Commission that it has forwarded thousands of corruption cases to the government, with the latter only processing a fraction of them. This council could be instrumental in following up cases, addressing the delays, and identifying the barriers preventing their completion.

It is naive to assume that any Prime Minister can tackle corruption alone without close cooperation between the different branches of government. Combating corruption is not a ‘one-man-show’ and this council could balance the distribution of the responsibilities amongst the different parties, which would allow any victory to be attributed to all members and not just the Prime Minister.

Certainly, if this council could coordinate with parliament, anti-corruption efforts would increase in effectiveness; creating an efficient route for parliamentarians to forward corruption cases to the council to address submissions quicker and more thoroughly. Nevertheless, we see parliamentarians strongly opposing this council, which aims to centralize the efforts against corruption.

The reason why the fight against corruption has been ineffective is due to the politicized nature of combating it. Many politicians in Iraq use corruption claims to score political points against one another by putting obstacles in front of anti-corruption efforts that target them or their political allies. They also refuse to support anti-corruption efforts of others in order to prevent political rivals from claiming such an achievement. One thing is for certain: a well-coordinated anti-corruption council would make these dirty tactics more difficult by limiting selective anti-corruption measures. This is why some politicians are resisting this initiative because it robs them from a lot of political maneuvering.

There is a lot of critique behind the High Council for Combatting Corruption, but the one that is most important is political will. If there is no political will to tackle corruption, then this or any other similar project will be useless. While the council as an anti-corruption tool in itself has potential, it remains in the hands of its members whether they utilize it in the best way possible or not.

Muhammad Al-Waeli

Muhammad Al-Waeli is a Ph.D. candidate in management focusing on leadership and reform in Iraq.