Among the most significant features of this year’s elections in Iraq has been the demise of sectarian rhetoric and the emergence of issue-based politics, with debate over the state of the economy taking center stage. But with two weeks to go before Iraqis head to the polls, many voters are in two minds over whether the country is heading in the right direction.

It is not surprising that identity politics has taken a back seat since the liberation of Mosul. Not only is there little appetite among an exhausted electorate for sectarian and ethnic incitement following four years of conflict that saw an unprecedented show of unity among Shias, Sunnis and Kurds on the battlefield, but the dynamics of political competition have taken a major turn.

Traditionally, sectarian and ethnic interests have largely framed the way leading Iraqi political parties compete against each other. But this has now changed for a number of reasons. Firstly, the Sunni leadership, comprising an old guard of political elite, is in disarray and confidence among Sunni communities is at an all-time low. Feelings of betrayal and abandonment are widespread among ordinary Sunnis who were led down a dangerous path in 2013, only to find that they had been swallowed up by the Caliphate. Meanwhile, the fallout from the failed Kurdish referendum has meant that for the first time, Kurdish parties will not be running under a united list and the emergence of new contenders in the Kurdistan Region could upend the traditional power centers held by the KDP and PUK. The dire state of Sunni and Kurdish politics means that for the first time, the leading Shia parties no longer view their Sunni counterparts – including the Baath Party – as a threat to their authority in Baghdad, nor the Kurds as kingmakers in the government formation process. For the Shia elite, their attention has now turned inwards.

The fragmentation of the National Alliance has meant that competing Shia-majority lists are seeking to carve out their own unique identities as a means to appeal to the electorate. And since sectarian identity is a non-issue, competing and often antagonistic visions for the country have emerged. Most notably, the fragmentation of State of Law Coalition, which overwhelmingly won the 2014 elections, has led to the emergence of Haider Al-Abadi’s Nasr Coalition and Hadi Al-Ameri’s Fateh Alliance. Given that all three lists are competing for seats from their original voter base, it stands to reason that issue-based debates will invariably emerge between them.

Abadi is campaigning on two key platforms: the successful conclusion of the war against Daesh that is predicated on his personal leadership as Commander-in-Chief; and his ability to keep the Iraqi economy afloat during the fiscal crisis. Nasr contends that had it not been for Abadi’s prudent approach, the war against Daesh and the fall in oil prices would have inevitably bankrupted the country. So salary cuts, hiring freezes, and reliance on foreign financial assistance were all necessary measures that Abadi undertook to save the country and ultimately win the war.

To the informed outsider, that may sound like a reasonable argument, but many ordinary Iraqis see things differently. A commonly heard view among voters in Baghdad and the southern provinces is that despite Maliki’s catastrophic blunders on the security front, the economy under his tenure was in much better shape and life was generally more comfortable. While this argument projects a fundamentally flawed understanding of the nature of Iraq’s economy and the realities of war, this form of cognitive dissonance is a major feature of the current election cycle.

In fact one of the most common critiques made by Abadi’s rivals and their supporters pertains to his handling of the economy. There is widespread dissatisfaction by public sector employees about the wage cuts that were enforced early on under Abadi’s tenure due to the fall in oil prices – something that Iraqis had not experienced in the post-2003 era. The argument goes that under Maliki, oil prices were high, but oil exports were half what they are today. It stands to reason, as the claim goes, that even if oil prices are currently half of what they were before 2014, the amount of government revenue between the two periods is roughly the same. This argument is of course erroneous on many levels, but the fact that it has traction among Abadi’s detractors is indicative of the sorts of competing narratives that are being put forward by rival coalitions.

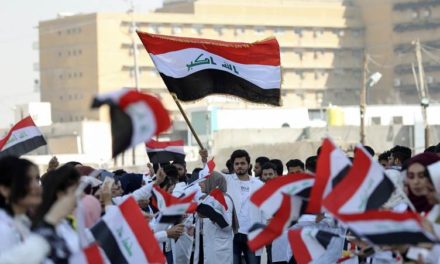

The extent to which these differences will lead to the emergence of substantive policy debates in the country is debatable. But the contrast in rhetoric with the 2014 election is stark. To put things into perspective, Abadi’s Nasr Coalition is fielding a total of 545 candidates in all 18 provinces. 30% of candidates are Sunni, 5% are Kurds and 10% are minorities. Similarly, both Fateh and Hikma are campaigning hard in the liberated provinces. With less traction for sectarian politics, it is only natural that competing issues, narratives and visions will come to dominate the election discourse.

Ali Hadi Al-Musawi

Ali Hadi Al-Musawi is an Iraqi analyst and contributing writer at 1001 Iraqi Thoughts.