Iraqi Sunni politicians gathered in Switzerland last week for yet another conference that was marred by mystery and intrigue. After conferences in Doha and Amman in 2015, and Paris last year, the “Geneva Conference” was held on February 15 and 16 in Montreux, 93 km east of Geneva. Like its predecessors, the event raised important questions about the intent of the organizers and whether it would produce any meaningful outcomes.

The European Institute of Peace (EIP) hosted the event, which brought together several controversial Sunni figures, government officials and a handful of foreign notables. The attendees included self-described businessman and known Qatari surrogate Khamis al-Khanjar, former finance minister Raf’i al-Eissawi, former Mosul governor Atheel al-Nujayfi, Mutahidoon Coalition chief Usama al-Nujayfi, al-Arabia Coalition chief Salih al-Mutlaq, Secretary General of the Islamic Party Ayad al-Samara’i, media mogul Sa’ad al-Bazzaz, and the governors of Anbar, Mosul and Salah al-Din. Foreign participants included former U.S. General and architect of the Sahwa, David Petraeus, former French prime minister Dominique de Villepin, and former director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency Mohamed al-Baradei.

Controversy

The conference caused a stir in Iraq, and for good reason, for it had all the necessary components to create controversy in Iraq: foreign sponsorship, toxic individuals and mystery. To date, the EIP have not issued a statement to clarify its role or define the conference’s objectives. In fact, not a single photograph or video from the event has surfaced so far. This created mystery and intrigue that opened the door for far-fetched theories about what the participants might have discussed in Geneva. Additionally, the participation of David Petraeus – a former military general and CIA director with close ties to Gulf regimes, and who worked closely with Sunni tribes during the Sahwa days, raises a lot of concerns for Iraqis. One Iraqi MP, State of Law’s Alia Nusayif, called the participants “suspicious, foreign-bankrolled figures who are implementing a Western plot to divide the country.” Another lawmaker dubbed the conference a “conspiracy” and went as far as calling for the attendees to be prosecuted.

The participants alone are a source of controversy; three individuals who reportedly attended have arrest warrants issued for them by Iraqi courts. The first of which is Raf’i al-Eissawi who is accused of running a death squad with his guards and who was convicted of corruption and sentenced in absentia to seven years in jail. Four of his guards were found guilty and sentenced to death in 2014. Another dubious character is Khamis al-Khanjar, who has an arrest warrant issued for him since 2015 in accordance with Article 4 of the counter terrorism law, accused of ties with ISIS. Khanjar famously called the Islamic State’s invasion of Sunni provinces 2014 a “revolution” coming to “liberate” Sunnis. Then there is Atheel al-Nujayfi. Last October, an arrest warrant was issued for Nujayfi in accordance with Article 164 of the penal code on charges of collaborating with a foreign country. Three Nineveh Provincial Council members had filed charges against him for facilitating the Turkish military presence in the province.

Divisions

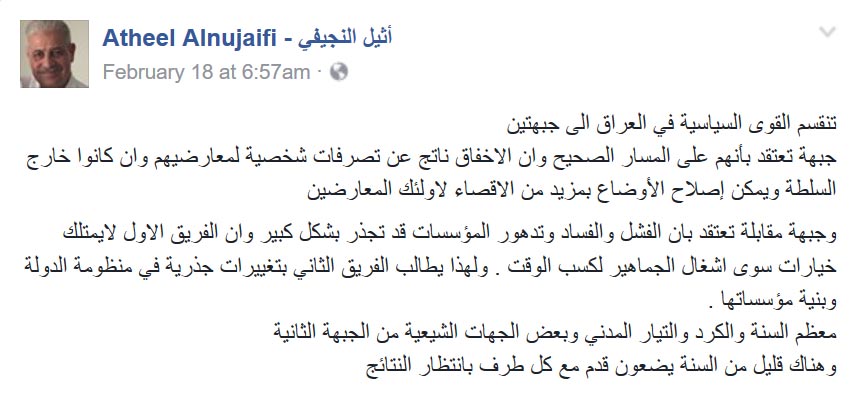

The conference highlighted disagreement amongst the Sunni political class. As Atheel al-Nujayfi put it in a Facebook post: “Political forces are split into two fronts. One front believes that they are on the right track and that failure is due to the personal actions of opponents… and an opposing front that believes failure, corruption and deterioration of institutions have taken root… [and] demands radical changes in the state system and the structure of its institutions.”

Nujayfi is right about one thing: Sunnis are divided, and the Geneva conference brought their divisions to the forefront. A quick glance at the list of attendees reveals that some important Sunni figures did not attend. Speaker of the Iraqi Parliament Salim al-Jibouri, head of Itihad al-Qiwa Bloc in parliament Ahmad al-Masari and al-Hal Bloc chief Mohamad al-Karbloui are just a few of those who boycotted the event. Even Jamal al-Dhari, a Sunni politician and nephew of Harith al-Dhari – the deceased head of the notorious Association of Muslim Scholars – snubbed the conference despite his established opposition to the Iraqi government.

The question is why did some Sunni leaders choose to boycott the Geneva conference and even condemn it publicly? Leaders like Jibouri, Masari and Karbouli learned from the media firestorm that erupted after the Doha conference. The barrage of criticism they received after the conference hurt their standing without giving them any positive tangible results. Three conferences preceded the Geneva conference, all of them unsuccessful. Additionally, these moderate Sunni leaders enjoy a good relationship with non-Sunni factions and have power over important government posts. Participating in a dubious, foreign-sponsored conference alongside three fugitives makes them susceptible to attacks from rivals and less viable allies to Shi’i partners. In other words, they have a lot to lose and little to gain.

Looking at those who did participate, it is evident that they are either former government officials who have become pariahs and are desperate for a comeback (Eissawi and Atheel Nujayfi) or current officials who let down their constituents and are anxious for a place in a post-ISIS order.

This raises another question: why did some seemingly moderate elected officials take part in this event? Because many of them are in a weak position politically after the fall of Mosul and are desperate for a countermeasure, albeit a hopeless one. The fall of Mosul and other Sunni cities generated discontent towards Sunni politicians from their own base. Sunnis feel resentful toward their leaders not only because these leaders stirred up the discord that contributed to the fall of those cities over the years, but because they failed to own up to their mistakes and did not do enough to help in the aftermath.

Consider Mutlaq, whose failure to manage the crisis of displaced Sunnis tarnished his reputation. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi places Mutlaq in charge of providing relief to displaced Sunnis who escaped ISIS. Abadi empowered Mutlaq by allocated a trillion Iraqi dinars for the project and delegated most of the PM’s powers to him. What did Mutlaq do? He reportedly pocketed most of the money, leaving IDPs with no shelter, food or medical supplies. It’s not surprising that Mutlaq, among other Sunni politicians, cannot step a foot in an IDP camp or any of the liberated areas without being showered with shoes and insults from his constituents.

The three Sunni governors who attended are also facing challenges of their own: Anbar governor Suhaib al-Rawi has been under fire for months and was nearly ousted multiple times; Salah al-Din governor Ahmad al-Jibouri is fighting a vicious political battle against his relative and Shi’i-backed MP Misha’an al-Jibouri and has been critical of Baghdad and the Popular Mobilization; Mosul Governor Nawfal al-A’goul is a second-line politician who lacks the needed political acumen to keep his job after ISIS is defeated unless he finds new allies.

Secretary General of the Islamic Party Ayad al-Samara’i is also venerable. Iraqi Parliament Speaker Salim al-Jibouri (Samara’i co-partisan, who he barely defeated in the election for their party’s leadership) is becoming more powerful thanks to his alliance with Abadi and his close relationship with Iran. Samara’i is struggling to find a role for himself beyond being the head of a party that is increasingly falling out of favor with Sunnis. The Geneva conference represents an opportunity to create an alternative Sunni front that counterbalances Sunni leaders that are more closely aligned with Baghdad.

In addition, the non-attendance of Jamal al-Dhari highlights clear rifts even within the ranks of anti-government figures. Al-Dhari heads a pressure group called Peace Ambassadors for Iraq (PAFI) and has been lobbying in Washington since 2015. Khamis al-Khanjar has also been competing for the attention of US officials by advocating for the de-facto breakup of Iraq as a means to carve out a Sunni region that he presumably expects to inherit. It is worth noting that al-Dhari’s PAFI played a key role in organizing the Paris conference so it is likely that Dhari and Khanjar have had a serious falling out.

Foreign sponsors

Another aspect of the conference that is worth considering is the international dimension. Again, while there is limited public knowledge of who attended, it should be noted that Dominique de Villepin’s presence was particularly significant since he was also a panelist at the Paris conference last year. The former French prime minister’s close links with the Qatari royal family are well known, and his private law firm has been advising the Qatar Investment Authority for several years. Since stepping down from the CIA, David Petraeus has also sought out lucrative commercial opportunities and joined KKR, a private equity firm, where he chairs their policy wing known as the KKR Global Institute. Unconfirmed media reports suggested that the purpose of his meeting with Prime Minister Al-Abadi last week at the Munich Security Conference was to discuss the outcomes of the Geneva conference.

The Sunni politician Dhafir al-Ani also told the press that the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) had been involved in organizing the event in Montreux. Again, this reveals a level of continuity with previous conferences, since USIP had also participated in the controversial conference in Doha in 2015. The event caused widespread outrage in Iraq after it was revealed that representatives from Saddam’s Baath Party had been invited, including radical armed insurgent groups such as the Islamic Army. At the time, it was reported that UN Special Representative Jan Kubiš had also met with delegates in Doha, which raises questions about the UN’s involvement in the Geneva conference.

In sum, the Geneva conference was a shot in the dark. A desperate attempt to internationalize the Sunni cause (perhaps akin to the Astana Conference) by individuals who have become too toxic for the political process and others who failed to serve their people and are searching for redemption. They wished to convince the international community that they – the outcasts, the fugitives living in exile or in Erbil’s hotels – are the only legitimate voice of Sunnis.

Contrary to what its organizers had hoped to accomplish, the conference simply reinforced the perception that the individuals who met in Geneva have nefarious intentions and are beholden to their foreign backers. Speaker Jibouri, Karbouli and the tens of Sunni figures who boycotted the conference understand that that no foreign power can force the change they want but Iraqis themselves. When Jibouri was asked about the conference, he answered: “Iraqi problems must be debated in Iraq. We don’t want to make the same mistakes that caused us to lose our cities to ISIS and left millions displaced. We must learn from this lesson.” He is right. And perhaps that is a lesson for those who gathered in Geneva.

Ihsan Noori is a political writer and a contributor to Inside Iraqi Politics, a political risk newsletter that specializes in Iraqi affairs. Twitter: @Thawra_city

Ali Hadi Al-Musawi is a contributing writer at 1001 Iraqi Thoughts. Twitter: @ahmusawi