(Protestors in Basra on September 7, 2018. Photo: Nabil Al-Jurani/AP)

Identifying the ideal structure for a federal Iraq remains a puzzle for Iraqis since drafting the constitution in 2005. As Iraq deals with reconstruction and reconciliation after defeating Da’ish territorially, it is important to continue the discussion around federalism until Iraq gets the right state structure and begins to govern effectively. The new government passed its hundred-day mark and as summer approaches, restlessness in many areas of the country grow, demanding greater autonomy from Baghdad. However, a lot of what fuels this frustration can be resolved with combatting corruption and empowering district councils, rather than empowering the already corrupt at the provincial level.

It is first important to understand the general set up of the current Iraqi state because it is neither a normal federal state nor is it a confederate state, rather one that fits in between. Iraq is a state with 18 provinces but not all of those provinces are equal in power. Iraq has a semi-autonomous region but that only makes up three of the 18 provinces and the other 15 provinces do not have the same political advantages as those in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. This makes federalism more difficult to implement, especially as there are many contentious articles in the constitution as interpreted by the Government of Iraq (GOI) and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) that need clarification from the Federal Judicial Courts.

Understanding the legal disagreements between Baghdad and Erbil would clarify the picture to many advocates in provinces like Basra and Kirkuk and reveal that obtaining regional status is not the panacea to their problems. The first assumption is that what is holding a province back is autonomy from Baghdad, when in reality it is corruption on all levels of government. As many have pointed out in the past, corruption in provincial councils and governors’ offices are no different to corruption at the Council of Representatives and federal ministries.

There are numerous governors from all provinces of Iraq that have either had to flee or been voted out by the provincial councils for corruption. Not to mention the lack of accountability at the provincial councils themselves. The same political parties at the federal level are the ones that run in provincial elections and a region would not incentivise them to perform better. Instead they would simply take advantage of less accountability. That is why, empowering government at the district level has been suggested as the best way to not only establish decentralization, but to achieve greater accountability, which leads to better governance.

Therefore, empowering corrupt officials by granting them greater autonomy will not resolve poor services in a place like Basra nor will it guarantee it more money from its natural resources. The KRG has been selling its oil independently of the GOI, the people see little benefit from it and continue to rely heavily on the support of the GOI’s federal budget. There are better strategies to implement decentralization and improve local governance.

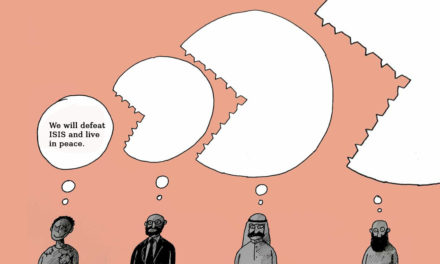

Empowering local leadership by establishing district councils will not only improve governance but also empower other minority groups such as the Turkmen, Assyrians and Yezidis. Decentralization does not necessarily mean deepening ethno-sectarian lines by pushing Iraq towards a more confederate state, which puts it at greater risk of dividing. Especially at a time where national sentiment is higher due to the nationwide cooperative effort to defeat Da’ish.

This leads to the issue of local security, which was raised as an argument for having Kirkuk obtain regional status. While the Kurdistan Region have their own security apparatus, this is not ideal in a federal structure and has created a lot of unnecessary tension between Baghdad and Erbil, despite the fact that the federal government pays the salaries of the Peshmerga. Becoming a semi-autonomous region would not necessarily allow Kirkuk to form their own security apparatus and the reason for the Peshmerga’s existence is because it predates 2003. That is why greater cooperation needs to be formed between the Iraqi Security Forces and the Peshmerga, and not add to the complexity of the issue by having more security forces from the establishment of other regions.

Having said that, the issue of forming local security forces needs to be discussed again, after initial talks were dropped over establishing a national guard due to the disagreement of their chain of command, whether they would be answerable to the governor or not. With the remaining questions of the Popular Mobilization Forces, it is important to revisit this issue. Debate over chain-of-command for the national guard is a legacy of a centrist Iraq, that will not be easy to overcome but is still possible.

On top of these discussion points, it is also important to note the powers at play that are not interested in seeing other regions come to fruition. The most significant are the Marje’ia, the Shia religious authority who do not encourage the idea of regionalism or anything that may lead to further division in Iraqi society. The Marje’ia have been more vocal in pushing for defeating corruption and improving services, rather than create further bureaucratic barriers for citizens.

It is still possible to implement strategies of decentralization to empower local governments and have them take more ownership of services, which would also allow the GOI to focus more on federal responsibilities like foreign policy and security. This will create healthy competition between the provinces to provide the best services, which if achieved, will decrease the calls for greater autonomy from places like Basra and Kirkuk and create more social harmony.

Hamzeh Hadad

Hamzeh Hadad is an Iraqi writer and commentator. He is currently a Master of Arts candidate at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs.