There is no shortage of analysis and writing that has been done on the Mosul Offensive; a battle that dwarfs any sustained urban combat in recent decades. To be sure, historians and military planners alike will spend years scouring the aftermath to glean what lessons they can from the Iraqi Security Forces’ triumphs and mistakes as well as what they portend for the future of warfare. For this article however, I’ve avoided questions of tactics and strategy or the political implications of the Islamic State’s defeat in Mosul. Instead, I would like to share the human side of the battle through the stories of several Iraqis I encountered while working in Mosul. In doing so, I hope to shed a light on the kind of bravery and sacrifice that made this victory possible.

Early one morning in January 2017, I found myself huddled on the roof of an abandoned gas station overlooking the Islamic State-controlled city of Tel Kaef north of Mosul. As the sun rose, the tanks of the Iraqi Army’s 36th Brigade, 9th Division belched smoke and plodded across the open plains ahead. By the afternoon, the ISIS fighters garrisoning the town were either dead or had retreated into East Mosul.

This was hardly a spectacle I had imagined myself witnessing when I first arrived in Iraq as a researcher six months earlier. But the day prior to that cold morning outside Tel Kaef, I had begun working as an ambulance driver for the Free Burma Rangers (FBR), an American-lead NGO that provides humanitarian and medical support to 36th Brigade.

The opportunity was only made possible through FBR’s Arabic translator, Shaheen, a young Iraqi Yazidi from Sinjar and my friend since before I had arrived in Iraq. When ISIS invaded his homeland in August of 2014, Shaheen and his family had sought refuge on Mt. Sinjar from the jihadists along with tens of thousands of other stranded Yazidis. On the plains below, ISIS summarily executed thousands of Yazidi men not fortunate enough to escape along with enslaving over 6,000 Yazidi women. For over a week, Shaheen remained there with little food or water and scarcely any protection from the summer heat, until a corridor was opened for the Yazidis to escape into Syria and then back into Iraqi Kurdistan.

Having not known Shaheen before 2014, it was difficult to tell whether his world-weary attitude was a product of his life experience or just a part of his nature. I was struck by what he said one time during lunch. When his fork fell to the ground, he casually picked up the utensil and continued eating without giving it a second thought. “Why not just get another fork?” one of our team members asked him.

He shrugged. “Man, I spent eight days starving on Mt. Sinjar and eating whatever little food we could find. You think a dirty fork bothers me?”

He did not suffer fools easily, be they Iraqis or Americans, and he took immense satisfaction in ridiculing me or other people on the team whenever we accidentally committed some social faux paus or asked him what he felt was a dumb question. “You are horrible!” he was fond of bellowing at whatever perceived slight we made against him.

Shaheen’s acerbic personality though concealed a deep passion he had for artistic pursuits. In addition to speaking Kurdish and English fluently, he was a life-long student of classical Arabic. He bided his free time by writing poetry, and under enough influence of alcohol, he would sing his lyrical poems out loud to our amusement. He spoke longingly of one day moving to Jordan or the United States after the war to get a Master’s degree in Arabic.

Shaheen was not a soldier in the Iraqi Army, but for all intents and purposes, he might as well have been. Shaheen arguably had the most dangerous job of any of us at FBR, accompanying our medics and the brigade commander at the frontlines. He carried no weapon on his person despite the perils, yet he was always right there where the action was. The soldiers loved him and treated him as one of their own.

He had little use for organized religion nor expressed any particular devotion the faith of his upbringing. Nevertheless, his deepest passion of all was his concern for the thousands of Yazidi women and children who remained in ISIS captivity. After Tel Kaef was liberated, 36th brigade pushed onwards into Rashidia, a suburb of West Mosul. A week after the Iraqi Army’s arrival there, Shaheen learned through his network of friends and associates that a kidnapped Yazidi child was being held in that very same suburb the brigade was headquartered in. After informing the commander, Shaheen accompanied a small party of Iraqi soldiers to the suspected home and rescued a seven-year old Yazidi boy without incident.

Back in the safety of the headquarters, Shaheen translated for us as the child weepily recounted his over two years in ISIS captivity. “He is from the village of Hardan in northern Sinjar,” Shaheen said. “His father and male relatives all disappeared after ISIS came, and his mother and sisters were taken to Syria to be sold as slaves. He was sold to an Arab man in Tel Afar and eventually brought here to Mosul.” It was a remarkable sight to behold; several dozen Iraqi soldiers and officers had crammed into the room to listen, and not a dry eye could be found among them. Tough brawny men; all reduced to sobbing as the young Yazidi boy’s litany of horrors were recounted. A few hours later, Shaheen and the brigade’s deputy commander accompanied the child to camp for displaced persons in the Kurdistan Region. There, the little boy was reunited with his grandmother after two and a half years; one of his only surviving relatives.

A month later, the 36th was stationed west of Mosul at the base of the Atshana mountain range. Slowly but surely, the Iraqi Army was tightening the noose around what ISIS fighters remained in the city. After stepping out into the dark motor pool one night, I noticed a solitary soldier doing maintenance on a vehicle by flashlight. After introducing myself,I learned that his name was Muhammed, a thirty-year old handsome Arab from Baghdad. His youthful features and delicate uncertain English gave him the appearance of being much younger though.

“Do you mind if I give you a hand with whatever you’re doing?” I asked him.

“Oh,” I would be so grateful, brother. I love America and American people.”

“I’m glad to hear!” I laughed.

As our conversation progressed, Muhammed spoke of his tragic childhood. “In the 90s, my older brother used to sell cigarettes on the street to make money for the family, because we were very poor. Saddam’s secret police found out about it and warned him to stop, but he kept doing it. Then one day, he never came home. A month later, we found his body lying in the street. He had been tortured and murdered by the police.”

For Muhammed’s family, the tragedies did not cease with the fall of the regime. “We were happy to see Saddam be overthrown. It made us hopeful for the future. And we were glad too when he was executed. To us, it was justice for what the regime did to my brother. But in that same year, my sister was killed while walking to school one day. There was a firefight between two insurgent groups in Baghdad and a stray bullet struck and killed her.”

In spite of such horrors being commonplace in Iraq at that time, Muhammed remained committed to creating a better life for himself than the one he had grown up in. In 2007, he and his girlfriend married, and he joined the Iraqi Army’s 9th Division to support a soon-to-be growing household of children. As a soldier, he saw combat in Baghdad and Basra against various insurgent factions, and from 2014 onwards, against ISIS.

In prodding for details about his experiences with the Army, he shared a story from the previous year’s campaign. “One night, I was standing guard in Ramadi at my post when fifteen ISIS fighters attacked our position. Thank God, we repelled them and none of us were hurt.” As I learned later from one of his comrades, Muhammed was understating his own contribution. He had in fact killed two ISIS attackers single-handedly that night. When the topic came up another time, Muhammed shared more details. “You know what’s strange? Both of those ISiS fighters were Chinese. They had come all the way to Ramadi to kill Iraqis. What had we ever done to them? I had never met a Chinese person before that!”

For the rest of my time in Mosul, Muhammed was one of my closest friends among the soldiers. He loved practicing his English with us and asking about life in America. “One day, I wish to take my family there,” he would say with a smile. He had more reason than ever to be pondering the future. At the end of April, his wife gave birth to their fifth daughter.

By May, West Mosul was completely surrounded, but Iraq’s Federal Police and Rapid Response Division were encountering stiff resistance in the city’s narrow streets. To increase the pressure on ISIS and ease the infantry’s job, the Iraqi high command ordered 9th Division’s tanks to assault from the northwest through the suburb of Kanisah. On May 4th, the attack began with 36th Brigade crashing into ISIS defenses on Kanisah’s outskirts.

Between the tank cannons, airstrikes, mortars, and machine gun fire, the scene was nothing short of apocalyptic. And to complicate what was already a chaotic situation, thousands of Mosul’s trapped civilians were attempting to flee to Iraqi lines during lulls in the fighting. Most made it to safety, but the less fortunate were deliberately gunned down by ISIS snipers still ensconced in the labyrinth of buildings and rubble in Kanisah. They made no distinction between man, woman, child, or infant.

Later that afternoon, just a hundred meters ahead of the most forward Iraqi position, an older man and young girl were shot by snipers and lay bleeding in the open. With the soldiers preoccupied with the ongoing fighting, one of FBR’s medic teams commandeered a Humvee and drove it out to the wounded civilians. Shaheen and Muhammed both accompanied them. After extracting the wounded into the vehicle however, the Humvee’s engine was disabled by near constant sniper fire. Taking it upon himself, Muhammed ran the gauntlet unscathed back to the nearest fighting position and grabbed another Humvee.

Within minutes, he had returned to the scene of the disabled truck with a new vehicle. As Shaheen stepped out of the Humvee to begin transporting the wounded to the other truck, he was immediately struck by a bullet through the abdomen and fell to the ground immobilized. Muhammed rushed out of his own vehicle to retrieve him. As he carried Shaheen to his truck, Muhammed was hit repeatedly by rounds from ISIS snipers throughout his body. In spite of this, he still managed to somehow drive the Huvmee back to the Iraqi lines where I and several Iraqi medics were present.

I was in shock when I saw my two friends emerge from the bullet-riddled Humvee, both badly bleeding. Despite the close proximity, the preceding events had transpired without my knowing, including when Muhammed came to get the second truck. We treated the wounds as best we could, and I drove them in our ambulance as fast as possible to the field hospital several kilometers back. Leaning against me in the cab of the ambulance, Muhammed drifted into shock. Fearing what might happen if he should fall asleep, I tried keeping him alert by practicing English as we normally did.

After dropping them off at the field hospital, I received a call that our disabled Humvee had finally been extracted and hurried back to the scene. Before leaving, I assured Shaheen and Muhammed that I’d be back shortly. When I returned to the hospital a half hour later with the old man and girl, there was no sign of either of them. They were already being life-flighted to Baghdad.

The next week passed with great anxiety for our team as Shaheen and Muhammed both underwent extensive surgeries. Meanwhile, 9th Division continued its assault deeper into Kanisah and wheeled south to besiege the last ISIS-controlled neighborhoods in West Mosul.

On May 13th, my final day in Mosul, the team was invited to attend lunch hosted by Lt. Col. Firas, one of 36th brigade’s battalion commanders. In addition to his native Arabic, he spoke perfect English, which he claimed to have picked up quickly while working with American forces during the Iraq War. Additionally, he was fluent in Kurdish and German. I listened as he commanded the room through sheer personality and effusiveness. The good colonel had a comedic swagger and arrogance about him; a personality trait healthily balanced by self-deprecating humor. It was rumored that his more straight-laced boss was no fan of his; not owing to any deficiency in competence or bravery, which Firas possessed in abundance, but because of his seeming lack of seriousness. By contrast, Firas’ officers and men were enamored by him and the reciprocal loyalty and cheer between them was unmistakable.

“You know, I have been a soldier for 23 years,” Firas said between puffing an ever-present cigarette and waving his tea cup in front of him. “Believe me, I’m ancient,” he bellowed with laughter. “It’s been war my whole life. Let’s see…the Kurdish rebellion in the 70s, the Iran-Iraq War.” With each conflict, he raised a finger to count them. “Then the Kurds again during the Anfal, Kuwait, the Americans, then the Americans again, al-Qaeda, and now ISIS. Since the day I was born until now!” he exclaimed, chuckling with a hint of sorrow.

“What year were your born?” I asked him.

“In ’75,” Firas answered. “My birth was a terrible omen for this country!” he cracked, roaring with laughter again. “Yes, the soldiering life has not been kind to my body.”

“Have you been wounded before?” I asked.

“Yes,” Firas responded. “I took shrapnel in the back from an explosion and also some here in the face,” he said while pointing to his left cheek and winking hard. “I don’t really see out of this eye anymore. And then there’s this side effect too,” he said with a grin while gripping his sizable belly with two hands. “I blame it on the Army!” Firas exploded into hearty guffaws again as did the rest of us.

The cigarette smoke from Firas and the other officers continued billowing as our collective attention was turned to the satellite TV. Planet of the Apes was playing, and the Iraqis were all terribly intrigued by the film. In one scene, a formation of ape soldiers marched and beat their chests as their commander swung from a tree. “Hey, it looks like one of those ISIS videos!” yelled Firas, turning towards the audience. In another scene, the old ape patriarch lay dying in his bed. “And that old one must be me!” Firas exclaimed to great laughter.

At the conclusion of the film, we all said our goodbyes to Firas and his gracious soldiers, and I departed Mosul for good. Two days later, those same soldiers advanced down the narrow alleyways of the neighboring Tamuz 17 district with their jolly commander directing them from the front. As Firas rounded a corner, an ISIS sniper’s bullet struck him through heart, killing him instantly.

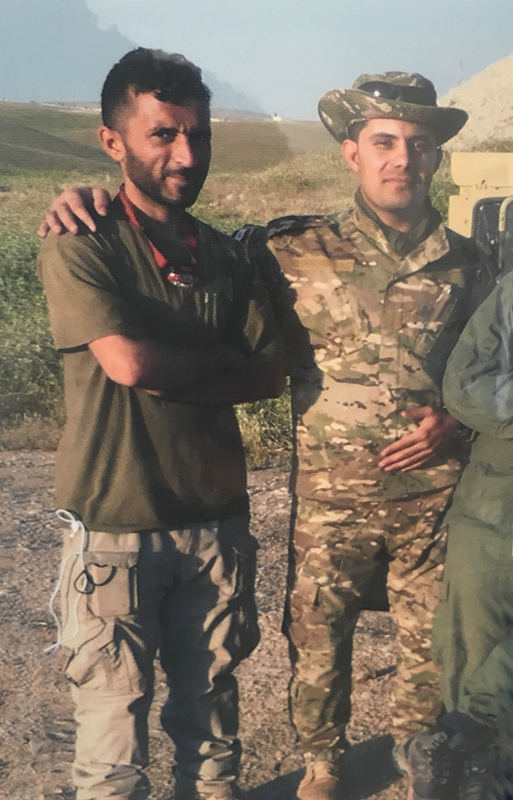

Our host, Lt. Col. Firas, two days before he was slain in Mosul

We received further bad news upon our return to Erbil in the Kurdistan Region. After enduring three surgeries, Shaheen succumbed to his injuries ten days after what proved to be his fatal wounding. By tragic coincidence, his home village of Tel Benat in Sinjar was liberated by Yazidi and PMU forces just hours before his death. I cannot know for sure, but I would like to think the news reached him before he passed away. His body was transported to Mt. Sinjar the next day, and he was finally laid to rest outside the Yazidi shrine of Sherfiden; the very same place he had sought refuge from ISIS three years prior.

Muhammed, the soldier who had rescued Shaheen at tremendous cost, survived his wounds and returned to his wife and five children to recuperate by the end of May. On the night before I departed Iraq, he surprised me by visiting Erbil to wish me farewell.

“I am so happy to see you, brother,” he said in his familiar innocent tone. He moved slowly now and spoke with a just a slight impairment in his voice. When I had last seen him, he lay dazed and blood-soaked in the field hospital. At that time, I feared I would never see him again. But now here he stood, alive and smiling.

All told, Muhammed had been shot six times; three times in the side, once in the shoulder, and once in the arm. A sixth round had struck him in the throat, missing his spinal cord by mere centimeters. We all watched in stunned silence as he showed the scars from each injury.

It was not long before our conversation turned to the most obvious question. “Why did you do it? I mean, you have your wife and kids and newborn daughter, and you still ran out to save Shaheen, knowing that you might be killed. Why?”

Muhammed nodded and thought for a moment. “I love humanity. It does not matter to me whether they are Muslim or Yazidi or Christian. And Shaheen was my friend. I could not just let him bleed to death there. I knew that I might die. Actually, I thought I was going to when I was first shot. But I told myself, ‘Even if I die, I will die trying.’”

Shaheen (L) and Muhammed (R) pictured several hours before their wounding

The next morning, Muhammed walked with me to my awaiting taxi to the airport. I hugged him goodbye, feeling more certain than our last farewell that I would see him again one day.

Muhammed’s long road to recovery raised questions about his future as a soldier; in some ways, not unlike the future of his country. Whatever awaits Iraq though, it will suffer no dearth of heroes to memorialize as it recovers from the calamities of the last three years. The nation’s citizens and non-Iraqis alike would do well to hallow the names and stories of its fallen. No better respect could be paid to their memory than to build upon the smoldering ruins a freer and stronger Iraq.

In addition to the thousands of killed and wounded Iraqis being a great loss for the country, several of them affected me personally, including Shaheen, Muhammed, and Lt. Col. Firas. Since returning home to the US, I have struggled to find the right words to pay proper homage to them or to impress upon other Americans the breadth of sacrifices made by these strangers in a far-away land. In coming to terms with friends now gone, I found little comfort in prayer or common platitudes or sympathetic well-wishes. Rather, I found solace elsewhere; in the words of Ancients long dead. In particular, I was struck by recently reading the funeral oration of the famous Athenian orator Pericles, who described the sacrifices of his countrymen defending democracy perhaps better than anyone else:

In the fighting, they thought it more honorable to stand their ground and suffer death than give in and save their lives. So they fled from the reproaches of men, abiding with life and limb the brunt of battle; and, in a small moment of time, the climax of their lives, a culmination of glory, not of fear, were swept away from us.

Bradley Brincka

Bradley Brincka is a former US Army officer and worked as a volunteer ambulance driver for the Free Burma Rangers in Mosul from January to May 2017. He is currently majoring in Arabic at Ohio State University in the US.